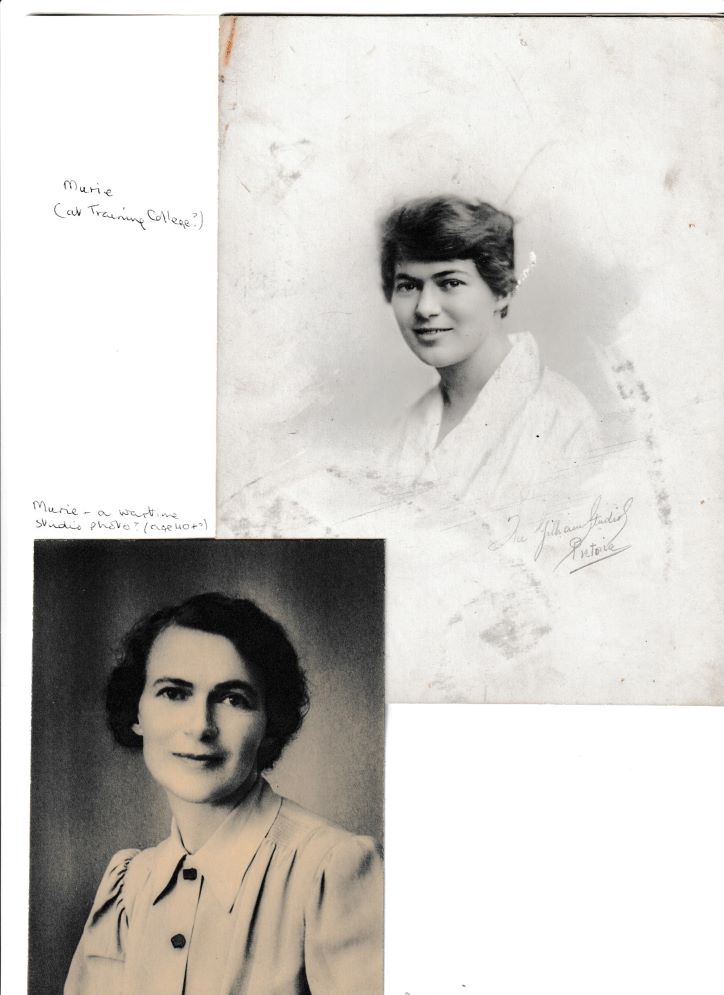

Murie’s life was dominated by 4 connected issues – family, money and the need for it, friends, and intellect. As a bright youngster she, like her mother, had to become a teacher because of lack of money. When her mother died unexpectedly with Murie in her first teaching job in Lydenburg, Murie became the emotional lynchpin of the family. And marrying Allon when she was 24, and having four children, resulted in her becoming the main or only breadwinner for much of her life.

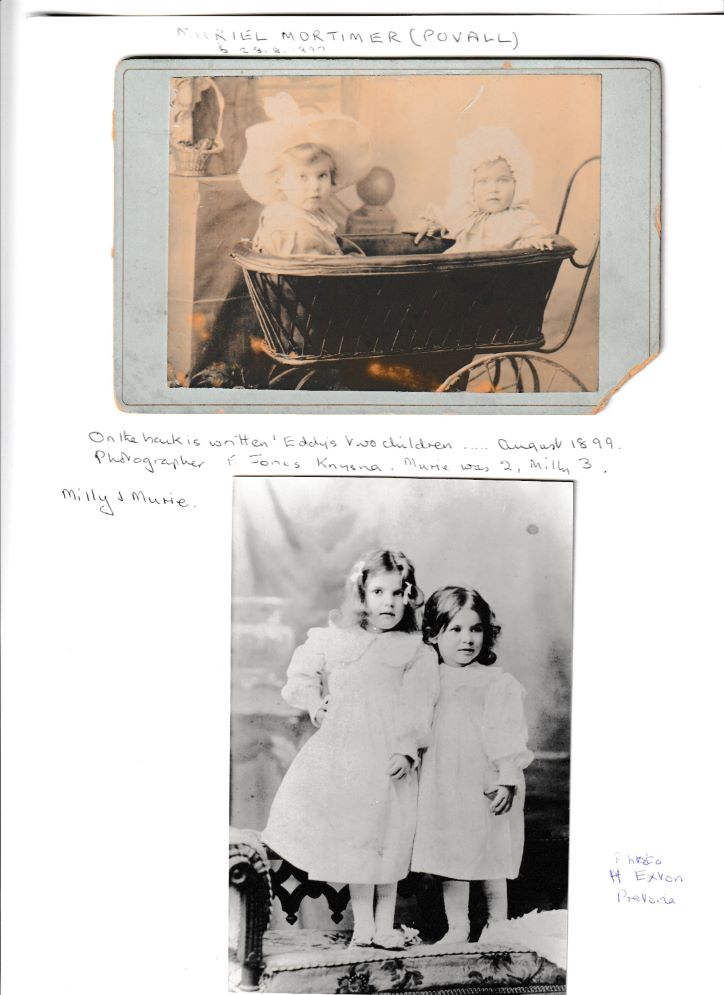

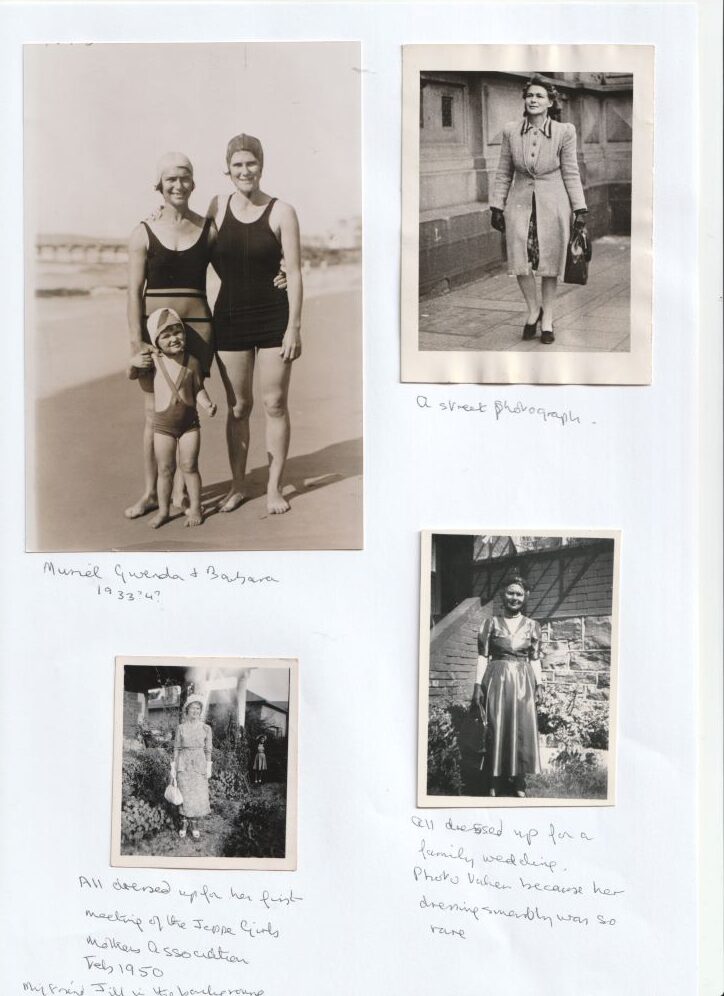

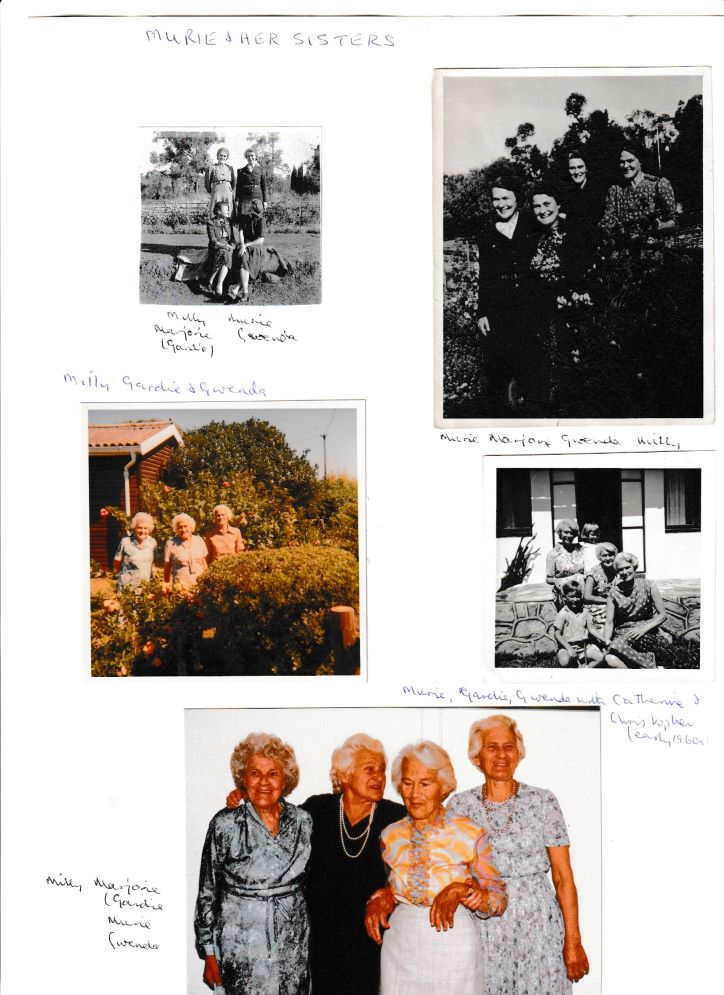

She was the second child of Lizzie and Eddie Mortimer, fourteen months younger than her sister Milly. There were 3 more children, Marjorie, Ted and Gwenda. At their mother’s death the family was broken up, Gwenda and Ted taken off to live with aunts, and Marjorie at 14 sent to boarding school. This left Murie at home with an alcoholic father and sister Milly with mental health problems.

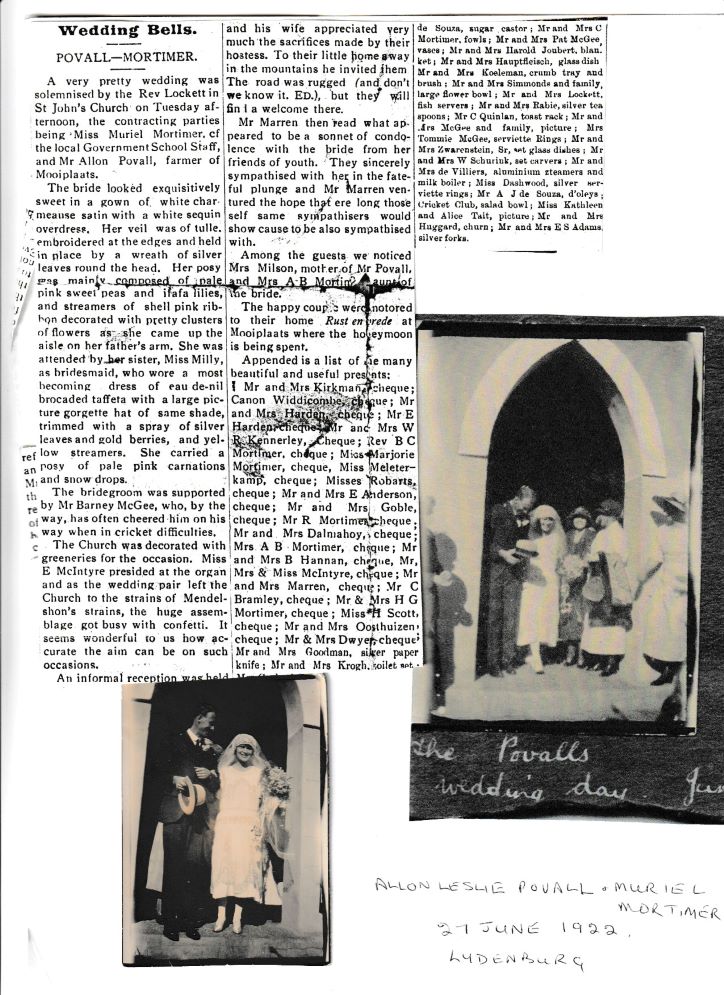

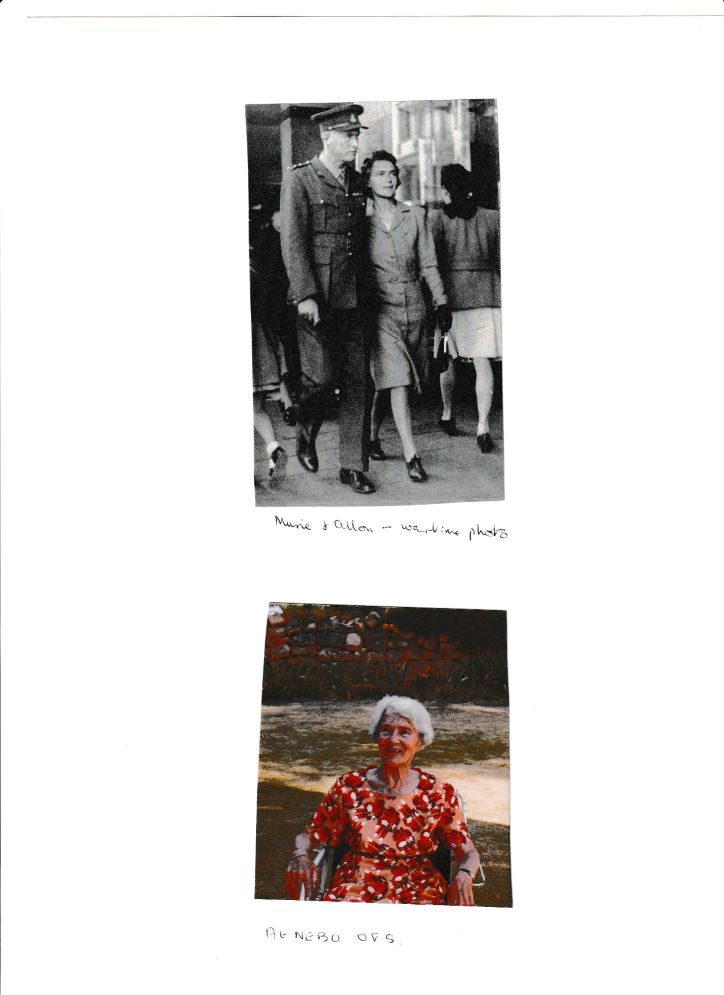

No wonder then that when Allon drove into town on his Harley Davidson and joined her at the cinema playing the music needed to give the atmosphere for silent films, she was swept away. But not to a traditional family life, with a breadwinning husband, and a wife at home, raising the children and keeping the house.

The start of her married life was to two stone huts on a farm outside Lydenburg where Allon strove to make a living, while she commuted weekly continuing teaching. This pattern continued even when she was pregnant with Peggy, and possibly also, two years later with Peter. Each week Allon took her in to town on his motorbike after the weekend, and when the bike broke down she walked along the river through wild country to get to work.

She taught most of her life, and as a married woman never got a pension. When she stopped teaching she got a morning job at Inland Revenue where ‘The Morning Glories’ were given thick files of unresolved cases to sort out. Her teaching started in Lydenburg, continued in Ermelo briefly when Allon gave up on farming and went to Johannesburg to try and earn a living, and continued in Johannesburg in between having two more children, Barbara and me.

Meanwhile her relationship with Allon continued until his death in spite of his love affairs, his refusal for them to put the money she had saved in the war as a deposit on a house. And then a few years later his need to try and save the world taking him to the UK for 6 years, [withdrawing his pension, and resulting in her losing her rented home and moving with the two remaining daughters into a boarding house], and his return to her after some years virtually destitute. When he was returning she had a mental breakdown but resisted a psychiatrist’s pressure to divorce him.

He put her through many terrible times, the worst of which, she told the psychiatrist [when pregnant with Barbara, their third child] when he told her he was in love with another woman. So she did not abandon him, but did stand up to him on some occasions. When he came back after the War and went to live for some time in Natal, and he wanted her to come and join him, she refused. And when he was in the UK and barely making a living he demanded that as his wife she must join him, [in letters I found very upsetting], she refused.

Later she told me that she felt that Allon, and his need to save the world, had something of value, and which obviously held to him. And she presumably loved him. Her devotion to him continued in spite of all her family being against him because of what they perceived as his terrible behaviour. But it takes two to make a relationship. Later, when I had worked through much of my own anger towards him, I deliberately made openings for her to talk about him, because I realised that there was no one in the world she could do this with.

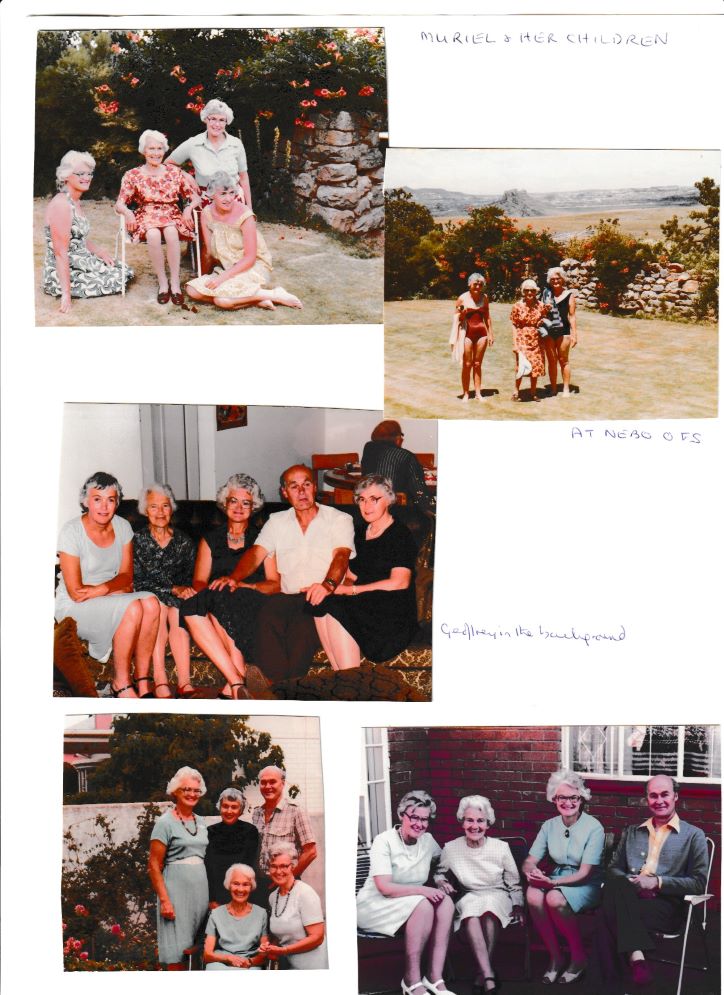

She was not ‘a baby’ person but was very involved with her grandchildren as they developed. Her granddaughter Jenny said “Granny was such a stable influence in our lives and always willing to step in and help when our mom was away or ill. I was always aware that she was a teacher as she was very strict on us but at the same time loved teaching us new things. I have fond memories of walking through Joubert Park with her and looking at art on display. She showed great interest in everything I did and knew exactly what subjects I studied and would ask what I was learning in each subject.”

Murie had a great need for intellectual stimulation. For many years this was provided by Allon, and The New Statesman, for which her childhood friend Bryna gave her a subscription. When I started learning about the history of art at University she and a small group of friends met to study renaissance art. Living in or very near the centre of Johannesburg, she started for the first time being able to go to concerts. Her children helped her become suitably dressed for these outings. We all gave her the present of a small fox-hair cape [which I disliked], and with my first pay cheque I bought her a black dress, both essentials in those days for women going to cultural events. Allon’s disturbance of this longed for life by demanding she come to England to join him, must have been very difficult, as also his return to South Africa later after she refused to go to the UK.

As Allon was an only child, we grew up knowing a lot about her family. She had an important role as the communicator and in many ways the lynch pin. From 1958 on, [when I came to the UK] I was kept up to date about many of the family goings on by her. But the men in her family, her uncle Leach, and brother Ted helped her in all sorts of ways, finding accommodation for her in Krugersdrop when she left Allon in 1931, with baby Barbara, and six year old Peggy and four year old Peter. And Ted and Olga gave Barbara her wedding to Peter Harrison in Randfontein

Murie and Allon had four children, and I used to think that her life with him could have been exciting and fulfilling had this not been so. She could have travelled around with him as his disciple seeing the world. However there were four of us, all of whom caused her problems in ways. Her relationship with Peggy, the first child and first grandchild, was never easy. Murie did not relate to babies, and with Allon demanding her attention, and Peter arriving less than two years after Peggy, and being outgoing, also demanding her attention, Peggy seems to have suffered. Barbara, born in 1931 to traumatic circumstances [Allon having said he was in love with someone else] can not have had much attention. Then [after Murie having gone back to Allon] I arrived at the end of 1934. Barbara was never well, having had rheumatic fever, and I had asthma. Murie reacted to the latter, with what I saw as annoying over-coddling, always anxious about me being warmly enough dressed when I went out . But her mothers death from asthma which broke up the whole family must have affected her relationship to me. She related to me also academically, making sacrifices to ensure I got to university, and being very interested in all I learned and did.

When later Geoffrey and I took her to Italy, her detailed notes served as our guide round Florence as to what and where we should go to view various masterpieces. And in 1961 [at the age of 66] she began travels to the UK and Europe, and later Canada. In Venice, much later, much to my and Geoffrey’s horror she decided she wanted to climb up windy stairs to the top of the Palazzo Neither of us were prepared to, and were greatly relieved when after just a few steps she decided to give up.

She thrived on any stimulation and gave a lot.

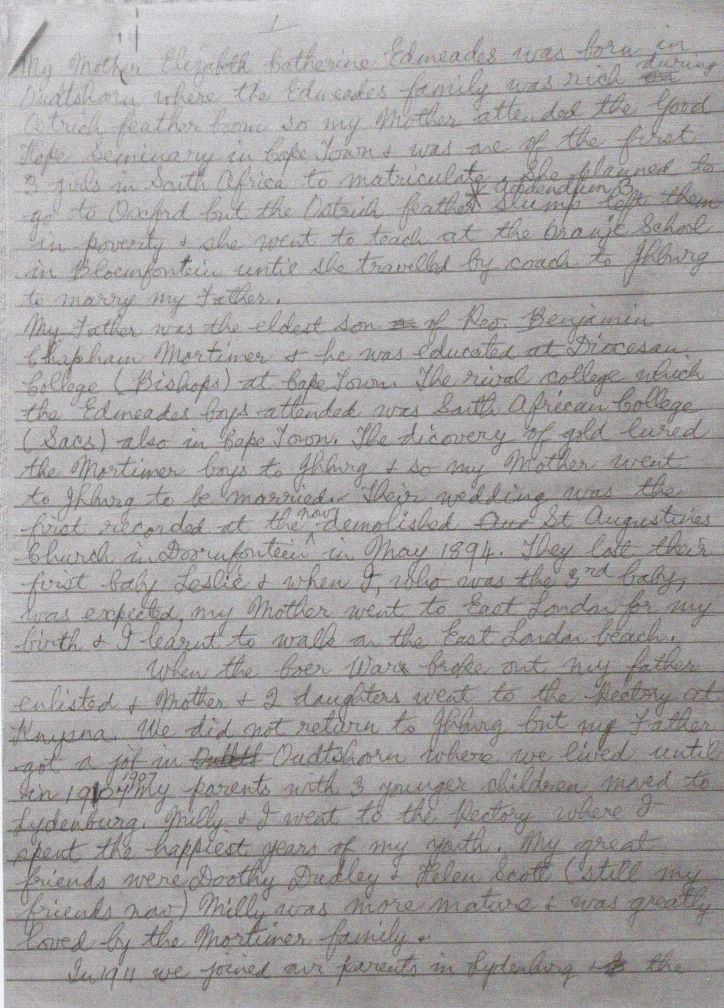

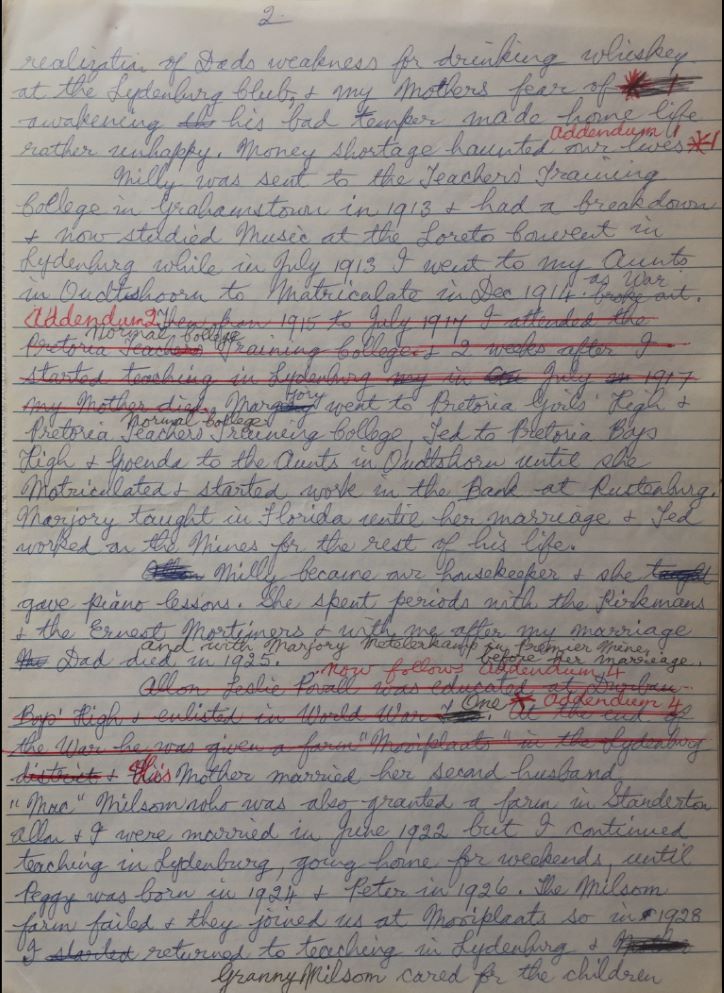

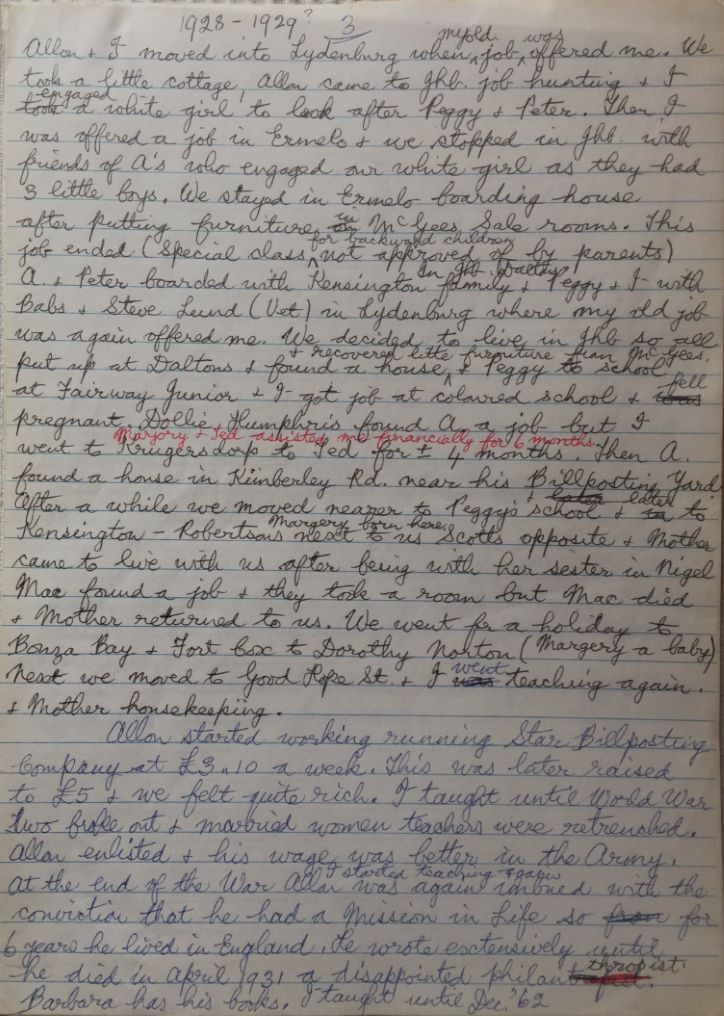

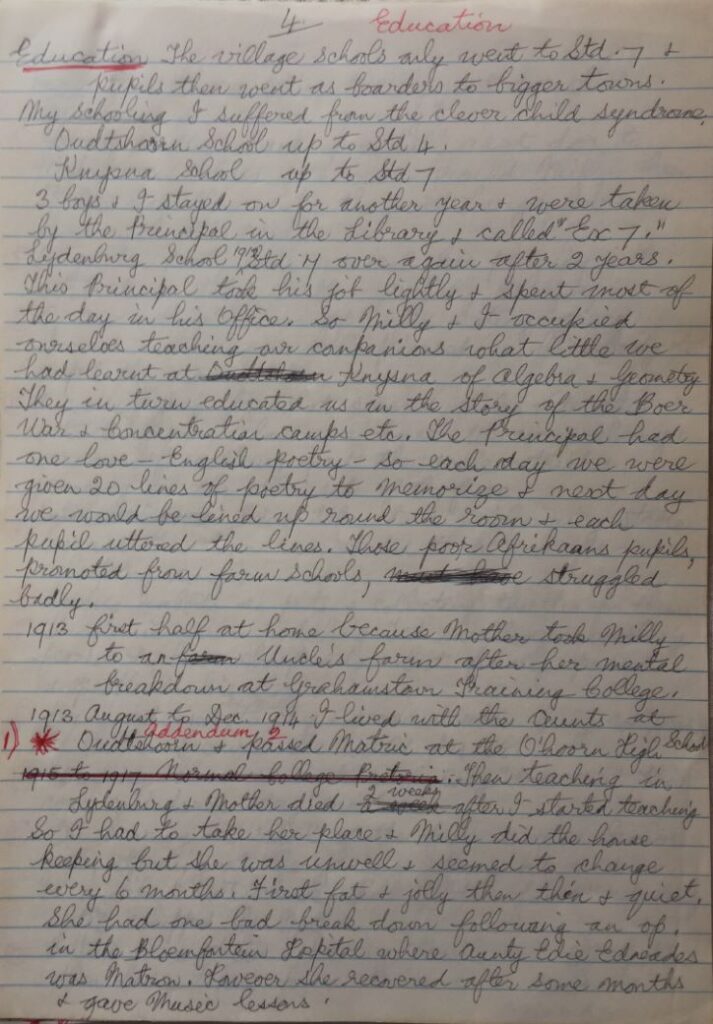

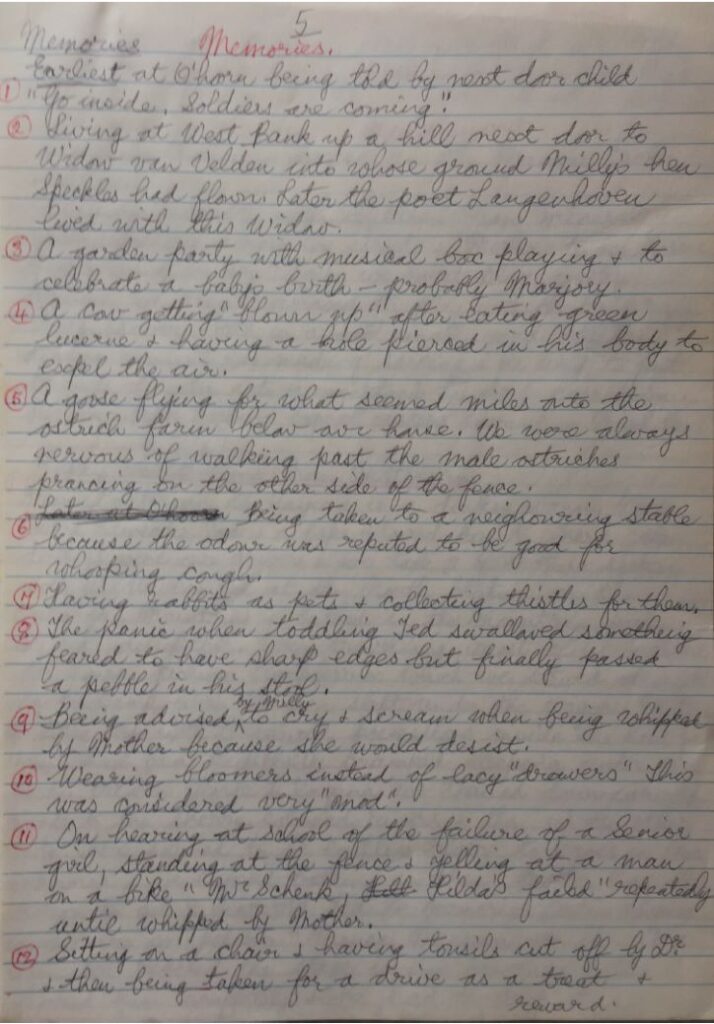

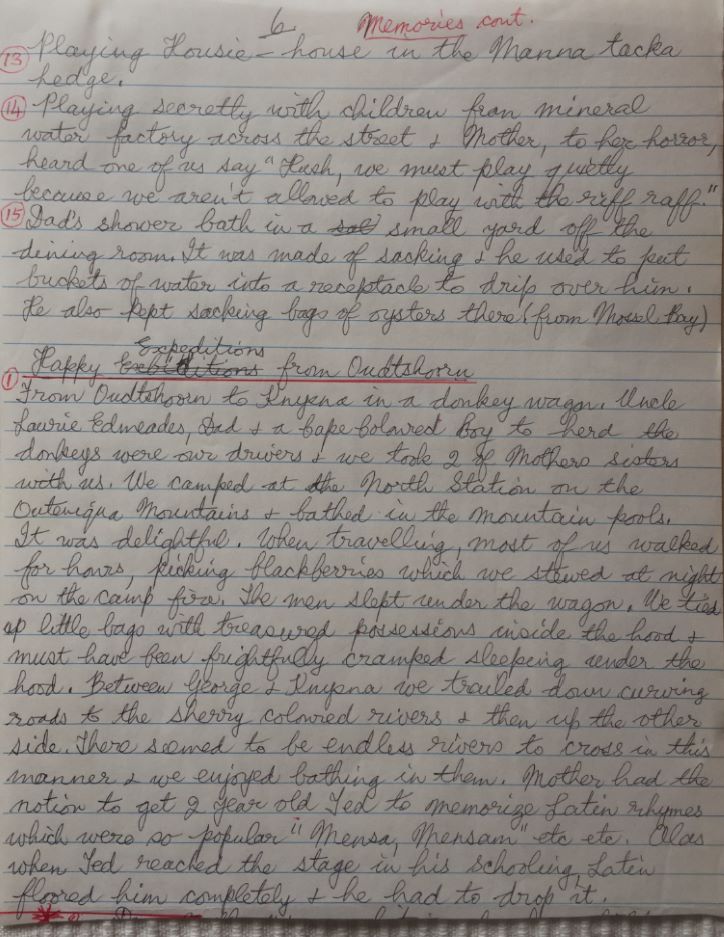

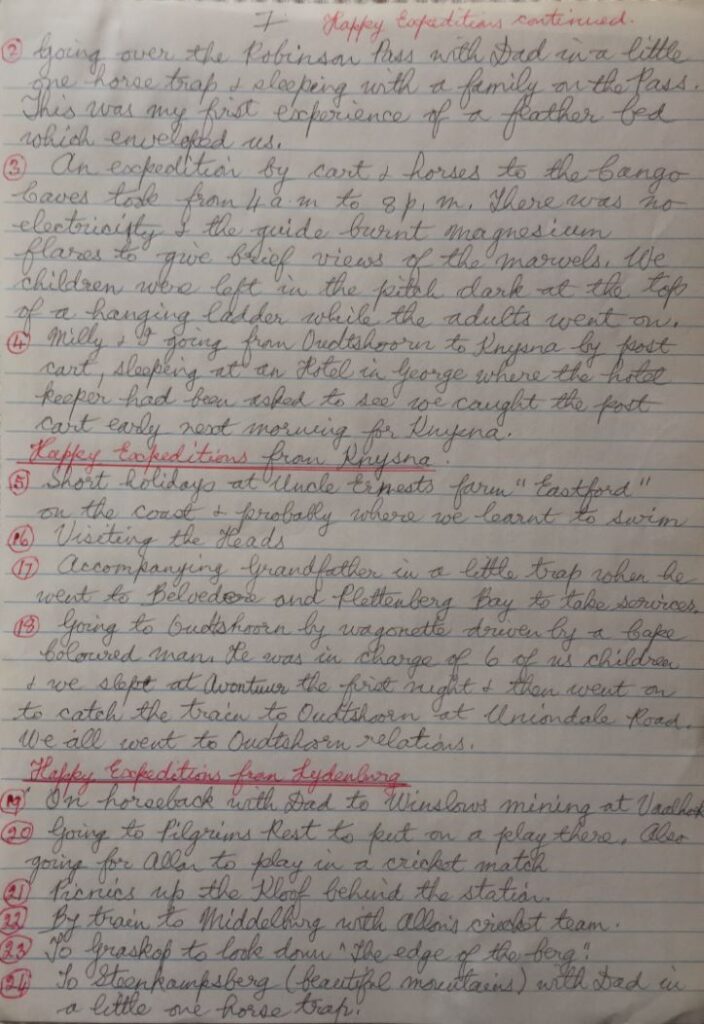

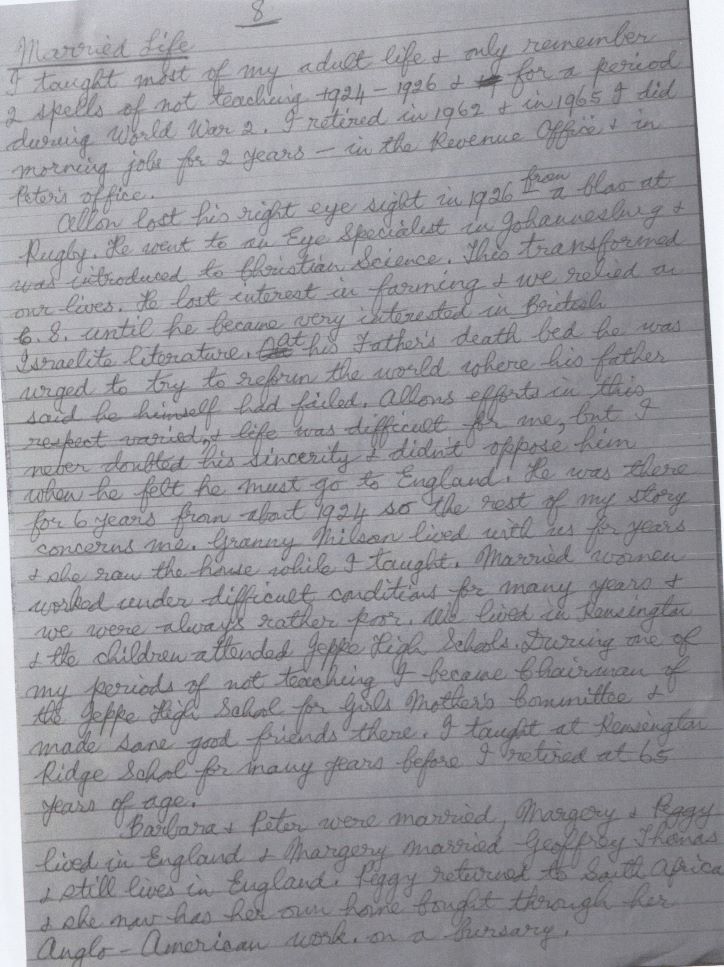

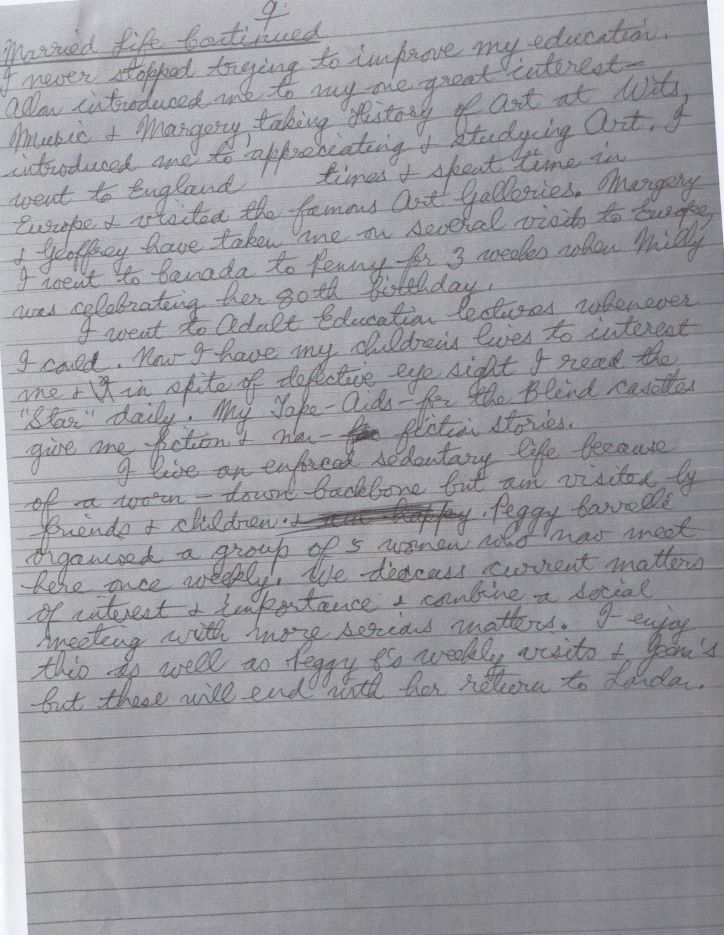

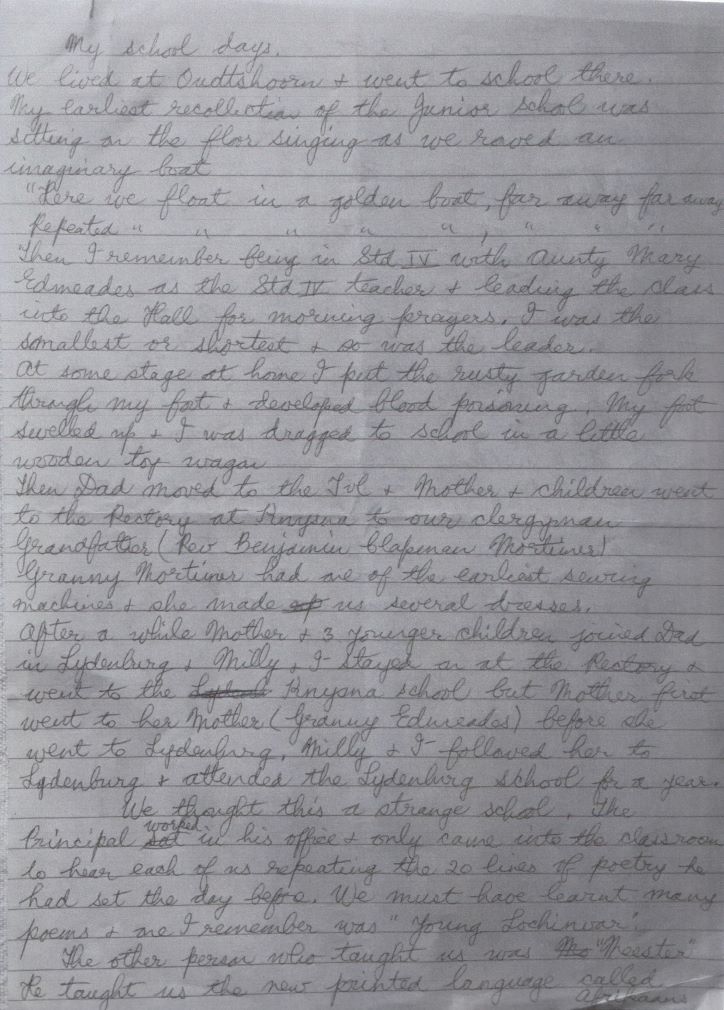

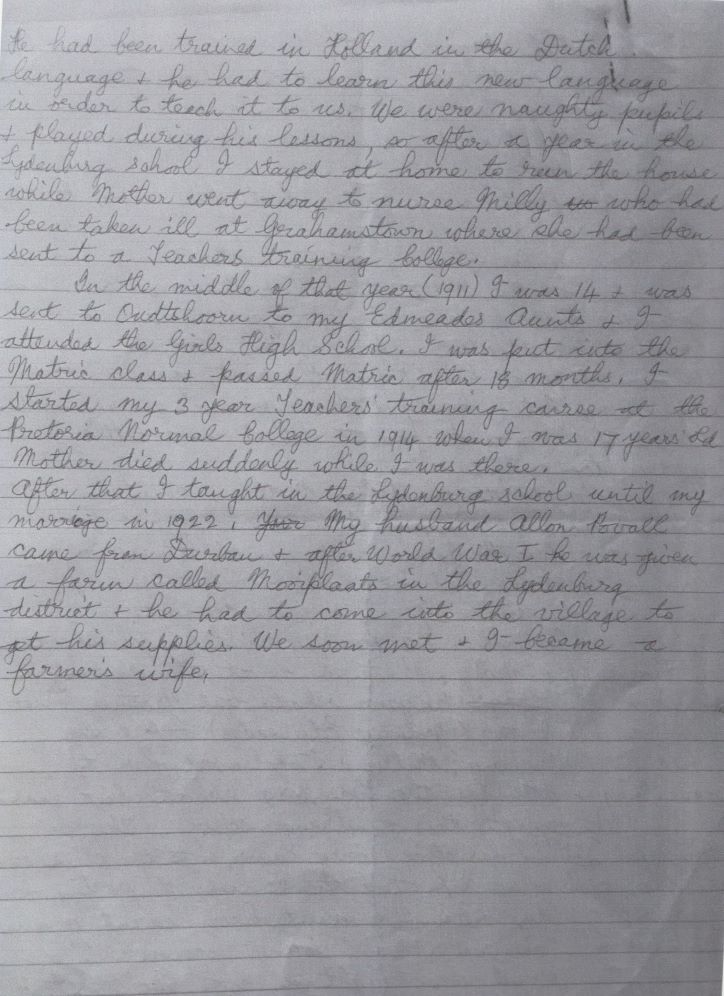

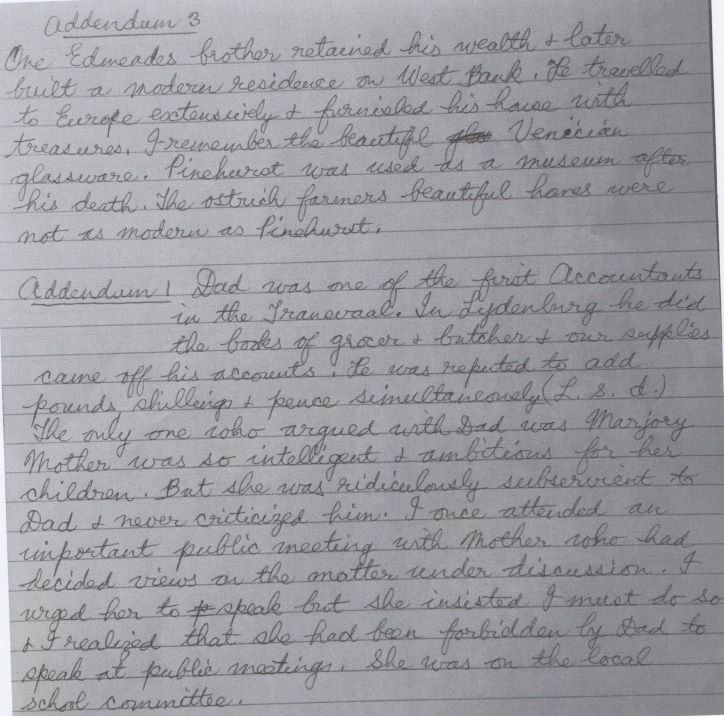

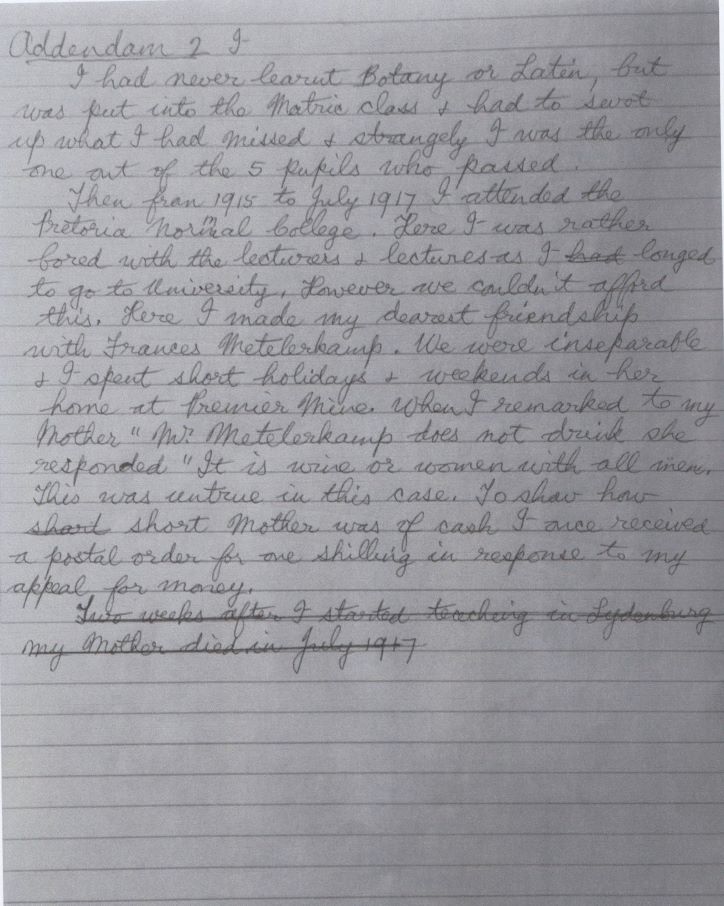

Murie gave the following handwritten note to Peggy.

We don’t know when she wrote it.