CHAPTER 1: THE FAMILIES BEFORE AROUND 1840

1.2.1 A brief history of St Helena, and of the Knipes there

1.4 The Mortimers in England [not done]

CHAPTER 2: EDMEADES FAMILY IN SOUTH AFRICA

2.1 The First Generation [1840-c1890]

2.1.1 The early years 1840-1860

2.1.2 Mary Ann Margaret Edmeades [nee Knipe] in South Africa

2.1.3 George Mason Edmeades and the development of the family businesses

2.1.4 George Mason Edmeades – the person and the family

2.2 The Second Generation FROM RICHES TO RAGS [c1870-1920]

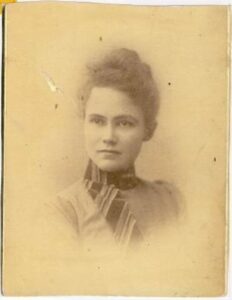

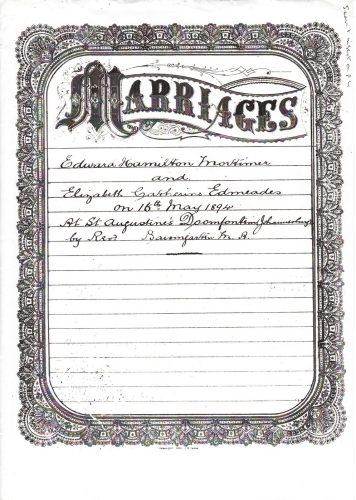

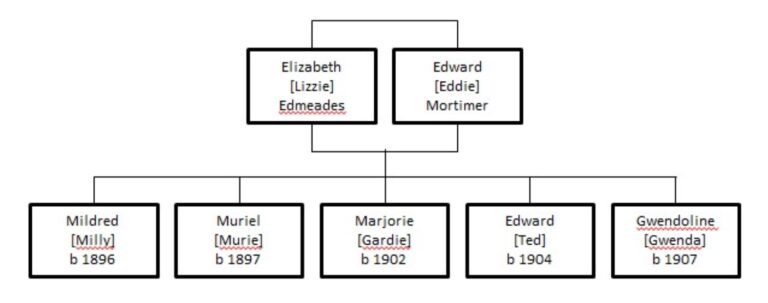

2.2.1 Elizabeth Catherine Edmeades [Lizzie] 1866-19171

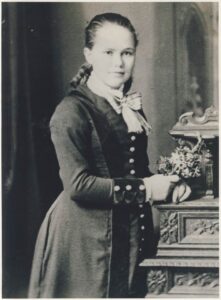

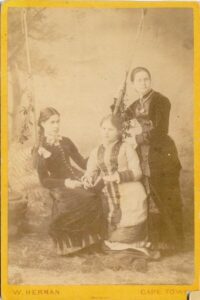

2.2.2 Lizzie’s siblings – ‘THE AUNTS’

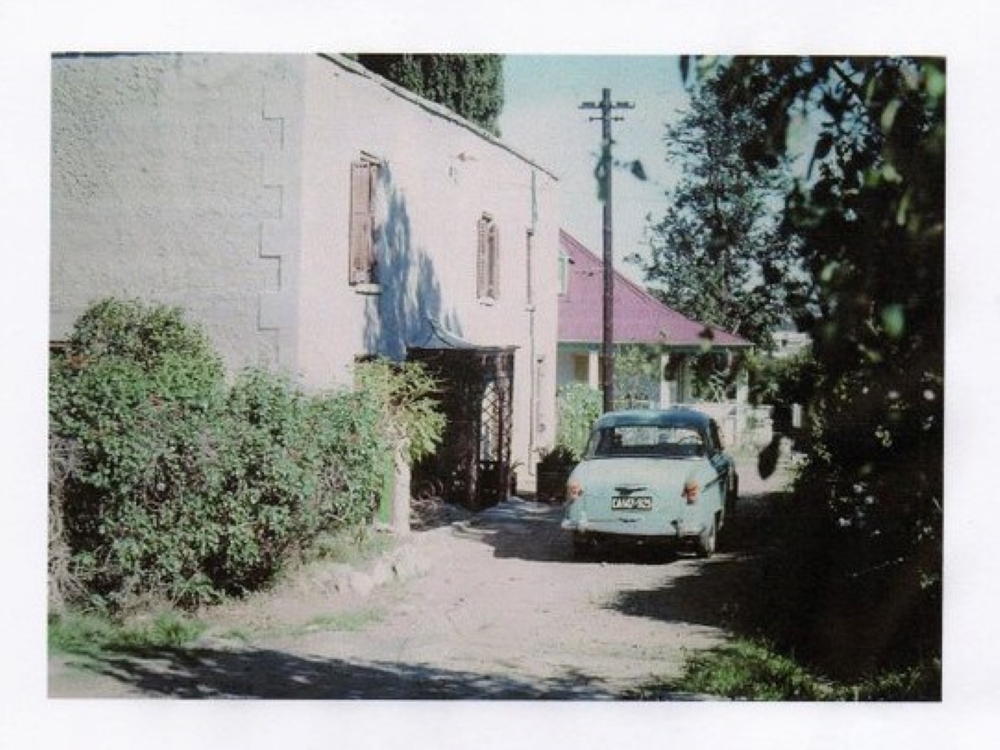

2.2.3 The house in Rudds Lane, Oudtshoorn

2.2.4 Lizzie’s married sisters

2.3 The third generation CHILDHOOD AND YOUTH [1900-c1925]

2.3.3 Growing up in Oudtshoorn, Knysna, Lydenberg

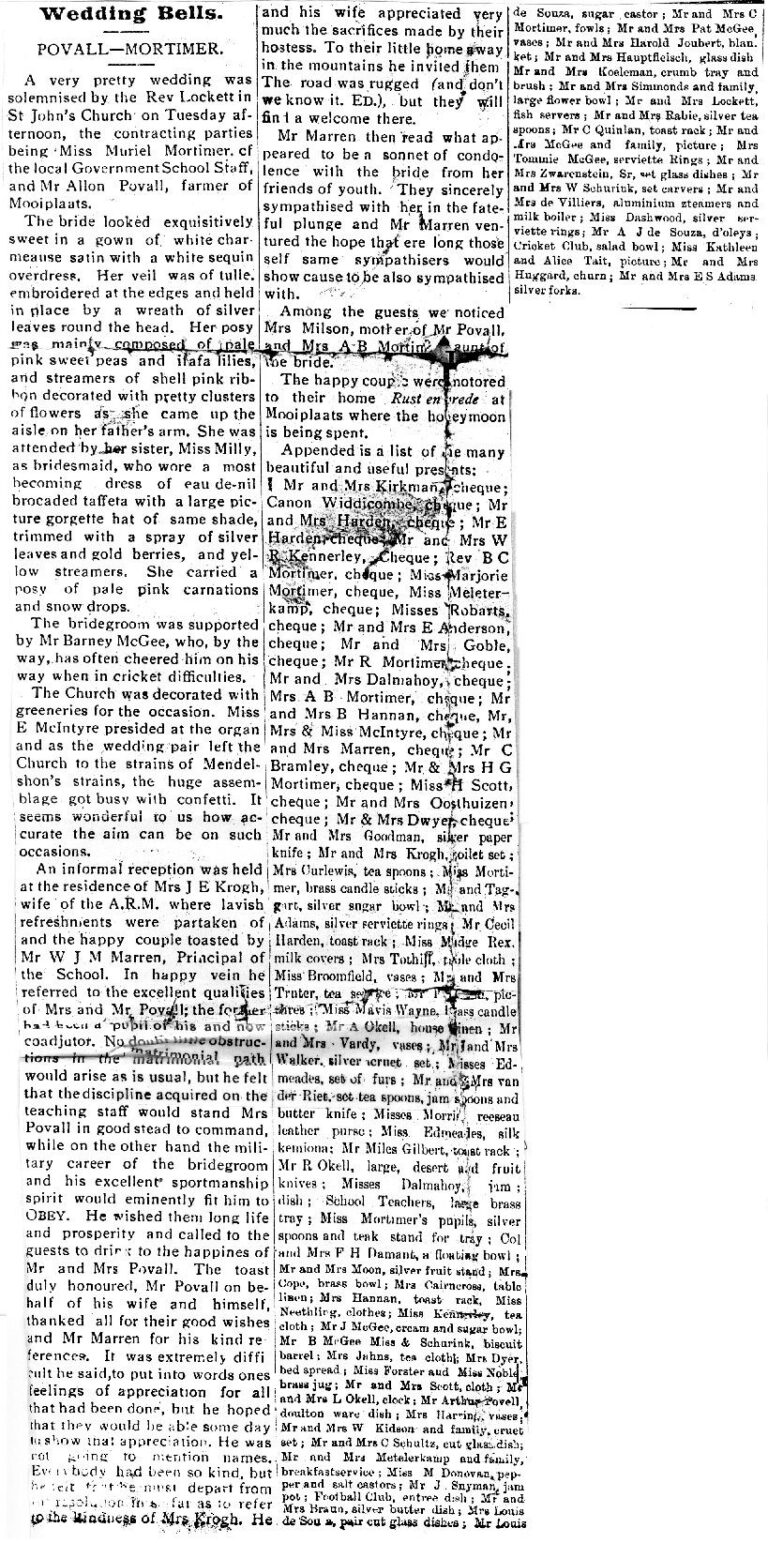

2.4 Allon and Muriel Povall [1921-1936]

2.4.1 Murie and Allon and the farm 1921-1928

2.4.2 Our visit to Lydenberg 2010

2.4.3. LIFE AFTER THE FARM for the Povall family [1928-1936]

CHAPTER 3: MORTIMERS IN SOUTH AFRICA[ not written]

3.1 The first generation 1855 –

4 The family of John Bazette and Martha Knipe

5 Other Edmeades data – William Penville Edmeades

6 George Mason Edmeades chronology

7 Other facts about GM Edmeades

9 Other data on members of the 1st family

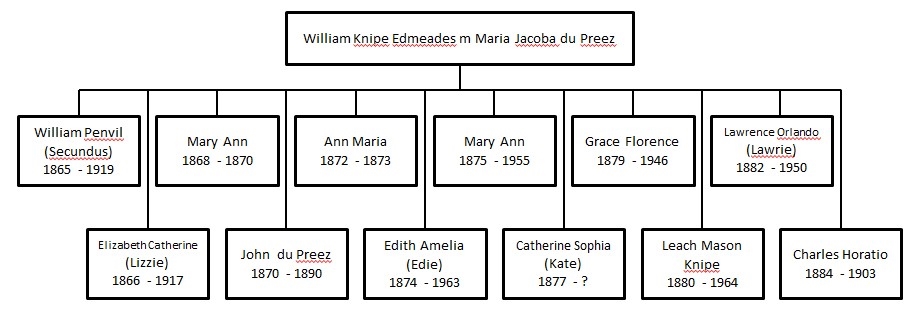

10 William Knipe and Maria Jacoba’s children

What follows is the beginning of what I hope may become an intriguing and entertaining story of the lives of part of one family, those Edmeades and their descendants who form a direct line down to me. I hope others will add to it, and this of course will inevitably widen its scope. So it may turn out with a very different shape from the way it started. But for the moment I am writing personally because that is all I can do. I have tried to write an interesting story from those sources I have to date i.e. the end of 2011. I started my story telling because I realised that I was forgetting many of the tales my mother, Murie told me of her life 100 years ago. So much had changed in the century which seemed worthwhile trying to capture. I was also intrigued to know more of the two quarters of my family history whose names disappeared i.e. the Edmeades and the Kidsons. I come from a family of strong women, but my grandmothers’ family histories seemed to get lost if only the Mortimers and Povalls were investigated.

Then the project widened, as my niece Lynette assiduously provided the beginning of family trees. And then through the internet I made contact with Bazett Meyer, the holder of an amazing Edmeades family tree and other information. Then a tape of my aunt Marjory was found which I transcribed, as also the transcription of an interview with my mother Murie, done by my sister Peggy. Having written as much as I could from these, another source came, my cousin Patricia’s daughter Jane in Australia who had unbeknown to us also been beavering away. And later, letters from Ian Edmeades to Lynette Bredahl, followed by feedback from my cousin David Metelerkamp, and from Jane Scott. These all provided a mass of information, some confusing, some conflicting, and much of it raising many questions about the context in which our predecessors lived.

This is of course the nature of biography, or any research. It tends to raise more questions than it answers. I wonder, for instance, what different versions of family history my various cousins have. Perhaps one day someone can put them all together, and sort out the resulting jumble. I have concentrated at this stage on trying to tie reminiscences and other information to known dates and places in order to provide the possibility of someone someday being able to place these people in the wider economic, political and social context in which they lived. I realise how little history I know as I write. I feel I have started developing a relationship and some understanding of some of those involved but am frustrated by my lack of historical and local knowledge to put their lives into context.

Edmond de Waal in ‘The hare with the amber eyes’ talks of some of the issues for biographers. How much does on elaborate from sources, or quote directly giving the provenance of the quote. The latter breaks up the story but give authenticity, whilst the former potentially distorts or misrepresents. I have decided to risk breaking up the story by giving direct quotes when I have them. He also talks of living on the edge of peoples’ lives by writing about them. Should one leave them be. I have indulged myself on the period up until around 1936, and then decided to stop in order not to ‘live on the edge of anyone livings lives.’ I hope I have succeeded.

The structure to date is chronological, but with periods overlapping. The key dates for the South African families are those of the first arrivals, 1688[du Preez], 1839 or40 [Edmeades], and 1865 [Mortimer]. To date I have done little on the Mortimer story although there is plenty of material available. I have divided the Edmeades part of the story [i.e. the du Preez, Knipe and Edmeades] into five sometimes overlapping approximate periods:

The sources to date are:

Edmeades family tree from Bazett Meyer [Baz], started by others, updated by information from Lynette Bredahl:

Tape recordings from Marjory Metelerkamp Milly Yates and Muriel Povall

Hand written notes from Murie

Reports of conversations of Gwenda Franz

Internet material on St Helena, and the Huguenots, and other history

Letters from Ian Edmeades to Bazett and to Lynette

Glynis Snell’s book on the Knipes of St Helena

Material collected by Jane Scott

Material I collected from two days spent in the archives of Oudtshoorn museum March 2004 e.g. from newspapers, and from their other archives such as material on dates from Rev Beddy

Additional information and feedback from David Metelerkamp, and Jane Scott and others

My personal memories

The story shifts constantly as new pieces of data come my way. Just as I have built up what seems to me to be a coherent story, something turns up which makes me rethink and rewrite, or to question my original story.

What is lacking from all this are letters from earlier generations, so often rich sources of material for biographers. With the families moving round so much all these possible sources were presumably destroyed long ago.

Margery Povall – 2002 [with later additions March 2012]

[Version as at March 2012]

It was exciting to find through Bazette Meyer that my family’s roots in South Africa go all the way back to 1688. This is because our great-grandmother was Maria Jacoba du Preez whose forebears came to South Africa as part of the French protestant diaspora. Maria Jacoba married William Knipe Edmeades, and was remembered by her older grandchildren [my mother and her siblings]. She, like so many women in the family was left a widow with young children. More about that part of the story later.

This discovery of centuries old family connections with South Africa provided the opportunity to speculate once again on my childhood memory of what was to me the somewhat strange physical appearance of my mother’s Aunts from Oudtshoorn. It was inevitable that over the years in South Africa there had been mixing across the colour lines, whether through ‘legal’ marriages, or other liaisons. I remembered that some of The Aunts from Oudtshoorn on their occasional visits to Johannesburg had distinctly sallow almost yellowy skins and flattish faces. Was this simply the result of sunshine and dusty environments? Later I wondered whether perhaps part of our heritage is Koi, or San? When I wrote this in an earlier version of this history, Bazette Meyer suggested that ‘a marriage to a Malayan or Indian slave was more likely.’ So we have two possible sources of the Edmeades appearance – the Knipes in St Helena, and the du Preezs. Will the day come in South Africa where people will proudly research their hidden family history across colour lines?

There are various [sometimes conflicting] versions of the du Preez history, but what follows is based mainly on a publication by the Huguenot Memorial Museum Franschhoek in 2000. It is by RH du Pre and was originally published as an article in Historia Vol 41 No1 May 1996. It is titled ‘Hercules des Prez and Cecilia D’Athis: founders of the du preez family in South Africa’, and seems the most indepth study of the family to date.

THE FIRST GENERATION

Context

The Edict of Nantes in 1685 resulted in an exodus from France of protestants denied the freedom to worship as they chose. South Africa was one of the countries these people went to, mainly in 1688 and 1689. The term Huguenot was not used to describe these people until much much later. They were known as French Refugees [Fransche Vluchtelinger], Fransche Reformeerde Vluchtelinger, Free French Settlers, emigrated French refugees or the French Colonists.

Having fled from France [usually from the north] to Netherlands most sailed to their new countries from there. In total 299 French Refugees arrived at the Cape, a few before 1688/9 and a few after. But in 1688/9 181 left Holland for the Cape on eight ships. This French influx made a huge difference to the white population of the Cape, constituting by 1730 one fifth of the population of the Dutch East India Company settlements.

When they arrived they joined a settlement of only 1000 people including children according to the census of 1687. One third of these were slaves, and 39 ‘knechts’ [white indentured laborers?] Simon van der Stel the Commander welcomed the refugees and promised to help them, which he did.

The refugees were housed and fed in Cape Town for some months because although the majority had arrived by August of 1688, they only left Cape Town in October, once the Cape winter was over. Simon van der Stel himself accompanied the main party and allocated land as they went.

He hoped the French would spur the Dutch on to greater effort! But he was also determined that the Cape should remain Dutch not become French, so tried to scatter the French amongst the Dutch settlers when allocating lands to them. This created friction with some of the French who wanted freedom to live in French communities, and to have their own congregation and church council. There was disillusionment too on Simon van der Stel’s part. The Commander became disappointed with his new residents. He wanted them to learn the Dutch language [teachers had to be bilingual in French and Dutch], and to learn Dutch values. Three years after their arrival, three years during which they had needed to have support, he said ‘We find that they still have the fickle nature and that they are very much like the Israelites, who in spite of God feeding them in the desert, still longed for the onion-pots of Egypt.’ By then he did not want any more French refugees, but wanted ‘hard-working and devout farmers and labourers such as the Dutch and High Germans’

The support during this period for the French refugees came from various sources. In 1690 they [including the des Prez] received money from the Charity Board in Batavia, and other supplies from the East India Company. Without the means of transport, getting supplies to them from Cape Town and selling their produce back to Cape Town was very very difficult involving journeys of well over 12 hours. Horses were only for the more affluent.

Cecilia and Hercules [1] – the first generation

Both Hercules [from here on referred to as Hercules 1 because many other Hercules followed] and his wife Cecilia were born in France, he around 1645 and she on the 5th November 1650. Hercules was born in Kortryk [or Courtrais, now just over the border in Belgium], and Cecilia in Artois [[was Kortryk in Artois?]. When they arrived in South Africa in 1688 with their family they were in their late thirties or early forties.

They and their six children [aged around 17 to 7] sailed from Vlissingen in ‘De Schelde’ on 19th February 1688, part of a party of 23 French refugees. The journey sounds quite terrible. The ship was 140 feet long and 35 feet wide. They are not allowed on deck at all during the voyage as 150 sailors had to move around in order to work the sails. They had been allowed to bring only money [of which they probably had little] and minimal personal possessions such as tools of their trade, and of course a bible or book of psalms. Passage and provisions were free, but the latter consisted only of salted meat boiled in sea-water, pickled fish, hard biscuit, rancid butter, dried beans and peas and small amounts of water, plus two glasses of beer or wine daily. They had a brief stop at Cape Verde to get fresh water but had to leave before being allowed on shore because of fears of pirates. After storms at sea, they endured another storm in Table Bay for eight days after anchoring, finally being allowed ashore only on 5th June. After nearly four months at sea surprisingly no one died or was even seriously ill.

This is said, in a du Preez family document, to be the signature of Hercules!

I can’t see it.

In Cape Town they were housed and fed by a Dutch burgher until they left for the interior in mid October. They along with all the others were given basic supplies for their new life. The Charity Board of the Dutch Reformed Church gave money for bread, ship’s biscuits, dried peas and salt meat. The Company provided planks for building shacks and also money. They also got other household necessities to last for six months [supposedly until their first harvest]. This included wheat for sowing, seeds and seedlings, and agricultural implements, and clothing. The money was an interest-free loan to be repaid with wheat. Some burghers also gave them money and goods, and promised sheep.

So off they went on 15 October with twelve wagons which were driven by soldiers. After overnight stops the Des Preez arrived 9 days later in the valley south of Drakenstein where they were allocated land.

So there the family settled – Hercules1 a linen worker by trade, his wife and five children, their eldest Elizabeth having married very soon after arrival in the Cape – veld covered in fynbos, minimal tools, displaced Khoikhoi and San around, and no means of transport. They named this inhospitable land Den Zoeten Inval. But life was hard. Their wheat harvest of 1688 was so poor they didn’t even bother to harvest it. They and the other French continued to receive support in the form of money and other supplies in 1689 and 1690. In 1690 the family had received 510 guilders from the Charity Board in Batavia, as also other financial support. Hercules1 got supplies from the Company on credit to the value of 583 guilders, and his son Hercules 2 also got financial support. The credit supplies the settlers received from the company once again included food, building materials, building tools, kitchen utensils and equipment, agricultural implements and supplies, hunting materials, livestock [oxen, sheep, poultry].

But after that, on the part of the ground suitable for the production of wheat and wine they had good harvests within 3 or 4 years. From then on the family seems to have managed better than many of their disillusioned fellow countrymen. So much so that there are still [or were recently] du Preez descendants on the farm.

In 1692, four years after landing in South Africa Hercules1 owned 23 cattle, had planted 6,000 vines, had harvested 25 bags of wheat, 25 bags of rye and 3 bags of barley, making the family one of the most productive and successful of the French settlers. Along with other more successful French they probably hired help from Dutch neighbours. They were forbidden to barter with the Khoikhoi but did get livestock from them in this way.

In 1719 thirty years after their arrival a commission was appointed to investigate the indebtedness of the French Refugees. None of the Des Prez were on that list of indebted people.

A farm De Zoete Inval still exists. It is the southern part of the original farm, and was in the 1990s still farmed by a member of the family Adrian Robert Frater. It produces estate wine. The northern part of the original farm is now called ‘Firwoods’, and at its entrance is the Du Preez Monument.

Hercules1 lived for only 7 years after his arrival, dying in 1695 in a good state financially, with his assets larger than his liabilities. By then they had 414 sheep, 35 cattle and even the luxury of a horse. They also had a knecht or white servant. So life must have been much easier, and almost comfortable.

Cecilia lived for a further 25 years, remarrying in 1700. She moved from Den Zoete Inval to the home of her new husband Pierre du Mont, Zoeten Dal in the Lemiet Valleij. She left behind her only unmarried child Francois-Jean to run the farm. After Pierre’s death in 1716 Cecilia probably moved back to Den Zoeten Inval. She secured, in 1718 the sought-after Drakenstein wine-and-brandy monopoly or lease, comparable to a wholesale liquor licence for which she bid a great deal at the auction of such monopolies at the Castle.

Cecilia died at her farm on 15 November 1720, aged 70, and was buried in the church in Suider Paarl, the church having been dedicated just five months before. She outlived 2 husbands, a daughter, at least 3 grandchildren, and one great-grandchild. She left Den Zoeten Inval to her youngest child, Philippe, with the other children also benefiting. The inventory of her belongings suggested some affluence including an ox-wagon, 133 head of cattle and 272 sheep. She also had two male slaves, and a female slave.

She also left a unique document. It is the Du Preez family certificate of church membership from the French Walloon church, dated 11th February 1688. This is unique, the only one preserved, and is in the Cape State Archives. Several attempts to access this site have failed. It seems to have been withdrawn.

There are reminders of Cecilia and of Hercules1 in Paarl today. There is a Cecilia Street. This, east of Paarl station, runs south across the N1 to the farm. Cecilia’s Drift on the Berg River ‘has existed from the time Den Zoeten Inval was established. There are two bridges at the drift, one on the old road and the other on the N1. The latter carries the new route through the Huguenot Tunnel in Du Toit’s Kloof to the interior’. There is also a suburb De Zoete Inval, and Des Pres, Datis, Hercules, Cortryk, and Schelde Streets. Courtrai which lies on the mountain side of the main road in Suid Paarl was also part of the original Des Preez farm.

THE SECOND GENERATION

Our line comes through their eldest son Hercules2, so we will concentrate on him. He sounds an interesting character. Born in 1672 in France and arriving in 1688 with his parents, at 24 [in 1696?] he married a much older Frenchwoman Marie le Fevre [Febure?] [born 1651, so aged 45 at the time], who came from Calais[Marck, Picardie?]. They had one son [Hercules 3] and one daughter. After Marie’s death in 1701 he married again [in 1702 or 3]?, this time a much younger woman, Cornelia Viljoen [Villion]. He acquired other farms, and became a member of ‘hof van landdrost en heemraad van Stellenbosch, captain of the ‘Burgher Kavallerie’.

But Hercules2 pitched into local politics and activism and got into trouble for this. In 1707 he was sentenced to a five year exile in Mauritius and a fine of £41.13s.4d, and certified incapable ever to hold a public or military position. He had refused to appear in court for his opposition to Governor Willem Adriaan van der Stel. Just before departure he, along with Adam Tas and other burghers, was released. He is described as stubborn and fiery-tempered. ‘The Du Prez’s were not easy people to get on with. They were easily irritated and were often at variance with some of their neighbours, yet they were never in trouble with the law’ [except hercules2!]

But he and subsequent Du Preez were becoming ‘Dutchified’ with the spelling of their name changing to reflect this. Their first names was also changing e.g. from Pierre to Pieter.

SUBSEQUENT GENERATIONS

Hercules 3, our next ancestor, was born in 1697 when his mother Marie was 46. He married Elisabeth Theron [possibly a cousin] [again in Paarl] when he was 26 and she 18. This was in 1723. They had at least four children. Apart from our ancestor Hercules Christiaan [Hercules 4] there were Jacobus Petrus, Johannes and Cornelia.

Their son Hercules [4] Christiaan was born three years later in 1726 [also in Paarl], and when he was 44 or 45 in 1771 married Regina Catharina Vogel. Apart from Hercules Johannes [Hercules 5] our ancestor, they had at least two other children, Cornelia Cecilia, and Johannes Christiaan

Hercules [5] Johannes was born two years after his parent’s marriage [in 1773] in Stellenbosch. He was described as a farmer and lived to the great old age of 76 or 77. When he was 27 or 28 he married Catharina Magdalen van Zyl in Cape Town, and they had 14 children of which our forefather Johannes Daniel was number 7 [at last an ancestor who wasn’t a Hercules].

[The other 13 were Elisabeth Maria, Regina Cornelia, Sophia Magdalena, Herculana Johannes, Jacobus Hercules [or Hercules Jacobus], Gideon Petrus, Cornelia Cecilia, Jacobus Petrus, Christoffel Philippus, Daniel Abraham, Maria Martha Anne, Johanna Philippina Jacoba and Catharina Magdalena]. They managed to find 30 names for their children, with only 3 duplications.

From this time on we know a little more about the wives of all these Hercules. Catharina [Hercules 5’s wife] was born in 1780 at Oudtshoorn Bossieveld, Robertson. She was the daughter of Gideon van Zyl and his wife Elisabeth Beukman. Hercules 5 died in 1850 [aged 77] at Goudini district Worcester [which is where Murie said her grandmother Maria Jacoba came from]. So the family had gradually spread out, acquiring land in places other than Paarl. His wife Catharina also lived to a great age, dying aged 80 or 81 in Stellenbosch. These were our great grandmother Maria Jacoba’s grandparents.

We move away [with some relief] from Hercules’s when we get on the information about Maria Jacoba’s parents, We are also moving further and further East as the family spread out away from Paarl. Her father Johannes Daniel was born in 1810 in the Swellendam district. He was a farmer at Andrieskraal in the Swellendam District. And when he was 23, in 1834 he married Elizabeth Catharina [or Katrina] Jacoba [Hendrika] Lourens.. She had been born in 1816 at Gouritsrivier district Mossel Bay. Her parents were Johannes Christoffel Lourens and Elisabeth Margaretha van Zyl.

[Elisabeth van Zyl was only six years younger than Catharina van Zyl, Johannes’mother, leading to the speculation that these two women were possibly related. Did Johannes marry his aunt [his mother’s younger sister], or some other relation of his mother’s?]

Johannes Daniel and Elizabeth Catharina had eight children, of which Maria Jacoba, our great grandmother, was the fifth, born in 1844. Her siblings were Elizabetha Margrieta, Hercules Jacobus, Catarina Magdalina, Johan Christoffel, Regina Cornelia, John Daniel and William Louwrens.

Maria Jacoba’s life

After all these names and dates about her family, what do we know about Maria Jacoba as a person? Very little unfortunately.

We know that when she was 20 she married William Knipe Edmeades in June 1864 at Humansdorp. But we don’t know how or where they met. And whether there was any reaction from either family to the fact that he was English speaking, and she Dutch or Afrikaans. We also don’t know when or why her family had moved to Humansdorp. It is a long long way from Paarl, and even a considerable distance from Oudtshoorn.

We know that she and William Knipe[WK] lived in the Humansdorp area for some years. He was in Oudtshoorn in 1863 but it was perhaps after that that he moved to pastures new near Humansdorp where he met and married Maria Jacoba. Already in 1864 he was declared insolvent in Humansdorp. He didn’t however appear to give up and return to Oudtshoorn because in 1872 he was described as a farmer on Langehoogte in the District of Humansdorp. So it seems that their first five children including our grandmother Lizzie were born there in Humansdorp.

WK seems to have returned to Oudtshoorn [perhaps on and off?], and certainly in 1877. But perhaps Maria Jacoba stayed in or near her family in Humansdorp?

Ian Edmeades gave some clues [in a handwritten note] as to where the du Preez family were and therefore where WK and MJ may have been. He says that his mother’s family, the Gerbers came from Germany and ‘settled in the Longkloof. My mother’s parents owned a very large farm across the Kouga River and mountains. The Provincial road went as far as the Kouga river and my grandfather had to build the road across the river and over the Kouga mountain to an extensive valley between mountains where he had his farmhouse with lands and grazing extending as far as the eye could see. The Gamtoos river has its origins where the Kouga and the Grootrivier converge. This is where the du Preez farmed. My parents bought adjoining farms about 10ks upstream from the du Preez and within 1k of the Grootrivier. My father bought his farm under the post world war I resettlement scheme and my mother bought the adjoining farm. The properties were about 3ks from Cambria. It was possible to walk from there across mountains to my grandfather’s farm. When I took Maisie[Ian’s wife] to see the farm some years ago we drove from Port Elizabeth through Humansdorp, then towards the Longkloof; ultimately we parked on the banks of the Kouga river and then went by four wheel drive across the river and mountain to the farmhouse in the valley beyond.’

Knowing so very little about Maria Jacoba our great grandmother, what follows are snippets from various people. In 1919 William Penvil [Secundus] our grandmother’s eldest brother was on his way to visit his newly married brother Laurie. He stopped off at his du Preez cousins at Andries Kraal, went down with flu and died there, Laurie having rushed over to see him. Presumably these cousins were Maria Jacoba’s brothers’ children. [Hercules, Johan, John or William]. The name Andries Kraal is interesting, because this had also been a name from the Western Cape history.

Murie remembered her grandmother as being ‘very small and very Afrikaans’, and coming from Goudini in Stellenbosch, a long way from Humansdorp. This is interesting because the connection with Goudini went a long way back to Maria Jacoba’s grandparents, but perhaps she [MJ] felt that this was where her roots were.

Gardie remembered her grandmother living with her daughters in a house up St Saviour Street in Oudtshoorn. ‘Granny was a very tiny little person and she had something radically the matter with her, and had to have the doctor come and tap something out of her [if you blow up and have a bad heart?] She was very delicate and the doctor perpetually calling.’ This must have been a few years before her death in 1911 at the age of 67. Having learned a few years ago that our grandmother, Maria Jacoba’s daughter died of asthma, I wonder if this too was Maria Jacoba’ problem. There was, and perhaps still is a lot of asthma in the Edmeades/du Preez family. I have asthma, as also did Bazette. So did his mother and her sister. And Ian said Lawrie did, and as a child Ian himself.

The only hints of Maria Jacoba’s Afrikaans or French or Dutch background in her children’s names were that one son was called John du Preez, and a daughter Anna Maria who died aged nine months, and another daughter named Catherine Sophia. All the others had very English sounding names.

So many questions which contact with the du Preez’ might answer. And a detailed map of the area or a visit would also help.

In November 2009 I wrote to all the five du Preez that I found in the Humansdorp area in the telephone directory. Three were eventually returned either ‘Unknown’ or ‘no such number’. Several addresses looked like names of farms. I did not try and phone, assuming they were probably Afrikaans speaking, and feeling unsure about my ability to communicate in a friendly and unthreatening kind of way. Thys du Preez, the holder of most information on the [male] du Preez history suggested that those that did receive the letter might have been old, and not felt obliged or able to reply. But he said there were two Jan Daniel du Preezs in Humansdorp, one born in 1960, the other in 1994. ‘Some Jan Daniels also had the nickname ‘Jan Jocka’ and I see the couple above christened their youngest son Jan-Jocka.’. He suggested other possible first names e.g. William Melville, Pierre Reniers, Philip Christophers and Renier van Rooyen.

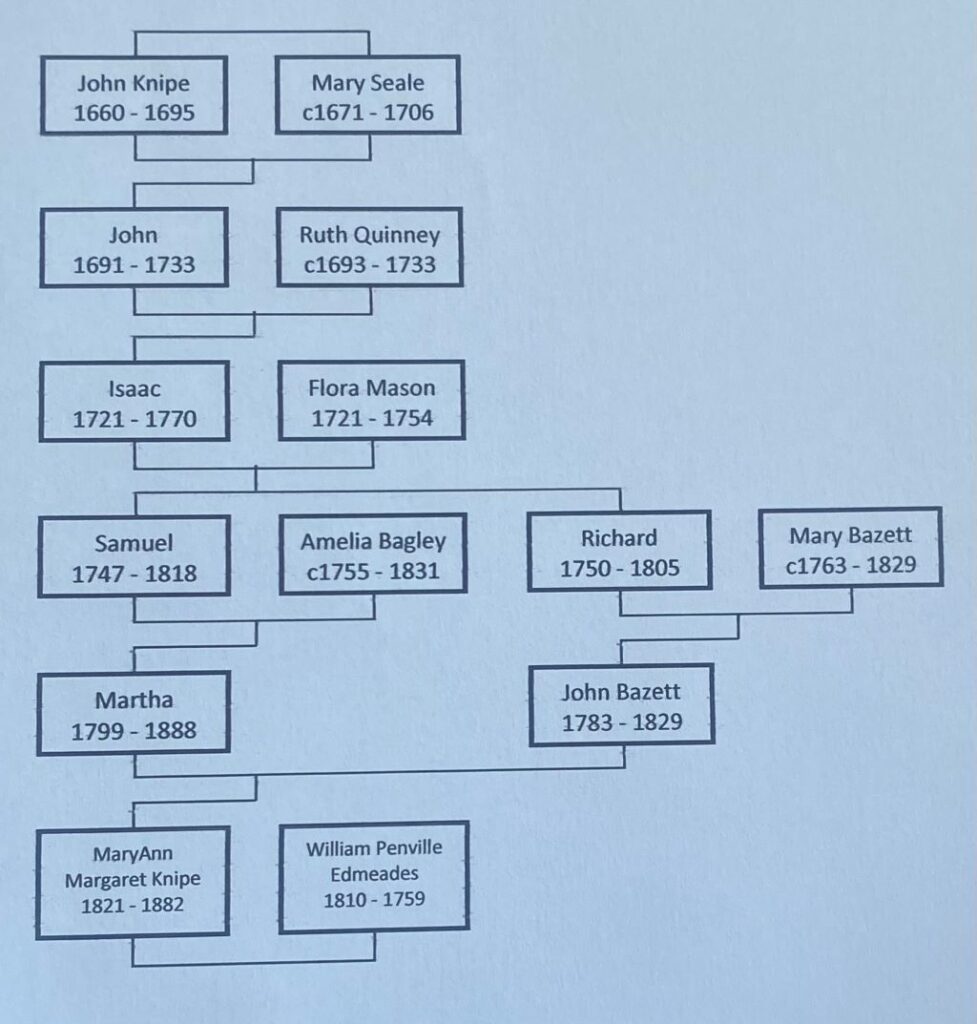

The first Edmeades’ to settle in South Africa did so from St Helena around 1840. Mary Anne Margaret Knipe, wife of William Penville Edmeades came from an old St Helena family. Her family had been on St Helena from the mid 17th century. We know quite a lot about them because of the painstaking research conducted by Glynis Snell. So although Mary Anne Margaret and her husband William Penville Edmeades left the island for South Africa around 1840, we can trace our Knipe family background much further back.

Britain had taken possession of the island in 1659 from the Dutch, and settled colonists there soon after. The island flourished under the East India Company as an alternative harbour for the sailing ships to that in Cape Town, and as a trading and refreshment, and whaling station, and then as the place of Napoleon’s exile, from 1815-21.

But early in the 19th century the economy declined, in part because slaves were set free, their freedom being purchased by the East India Company apparently for £62/17/0 in total. Before this, in the 1814 census the Island had only 694 civilian whites and 933 civil and military staff, but 1200 blacks [presumably slaves as there were also 420 ‘free blacks’], and 247 Chinese.

It became a Crown Colony when the British government took over the administration of the island in 1834 after the East India Company failed. They fired all employees of the company, and in 1838 removed the subsidy to the island, which had previously been paid by the EIC. In 1836 Darwin found the island poor, with, he estimated, about 5,000 inhabitants. The economic conditions were therefore very hard from the 1830s on, and from 1838 there was a mass exodus of 2000 young people. Families and more than a hundred young men emigrated to South Africa. This included our ancestors, Mary Anne Margaret [nee Knipe] and her husband William Penville Edmeades.

Mary Anne Margarets’ family had been on St Helena for more than 150 years when she was born in 1821, the first Knipe, John [born around 1660] being there by 1682 and marrying Ann Seale there in 1689. He [and probably she] had been born in England..

A contributor to the St Helena forum on the Internet said the Knipes seemed to have married into almost every other family, perhaps not surprising, as the non-slave population was quite small. Family names from the Knipes which were in great-grandfather’s brothers’ names and those of subsequent generations were Mason, Bazett, Leach and Orlando. My great-uncle Leach Edmeades, for example, was christened Leach Mason Knipe, and his son was Mason.

There is an interesting tale in Glynis Snell’s book involving a dispute between John and a woman who claimed he had promised to marry him [when he was about to marry Mary].

We have his will dated 1695 in Appendix 1, leaving money and cattle to his mother if she came to the island, and his estate to his wife and two children, [his third child being born after he died]. No signs of affluence.

Our line down to Mary Anne Margaret Knipe who with her husband William Penvil [or Penville] Edmeades came to South Africa, continues through four generations. These are

– John and his wife Ruth Quinney

– Isaac [and his wife Flora Mason and their two sons Samuel and Richard

– Samuel and his wife Amelia Bagley, and [somewhat confusingly in terms of straightforward family trees], also Samuel’s brother Richard because their children married each other.

– Richard and his wife Mary Bazett, parents of John Bazette Knipe

– Martha [b 1799] and her husband John Bazette Knipe [b1783]

– Mary Ann Margaret [MAM] [b 1821]

So Mary Ann Margaret’s parents were cousins.

We have quite a lot of information on her grandparents, some of it confusing, but giving a picture of life in St Helena at the beginning of the nineteenth century

RICHARD AND SAMUEL KNIPE, MAM’S GRANDFATHERS

Her two Knipe grandfathers were sons of Isaac and Flora, Samuel three years older than his brother Richard.

Samuel seems to have flourished on the island. In 1810 he owned nearly 200 acres, half freehold half leasehold. He owned 10 able bodied slaves, and 2 infirm.

But his brother Richard reportedly died bankrupt in 1805. They had both owned many different plots of land, but between 1776 and 1800 Richard was leasing out many pieces of land to others.

Richard had become an East India Company Cadet in 1774 aged 24, was promoted to Lieutenant in 1775 and was’ for many years a member of St Helena military establishment’. In his will of 1805 he is described as ‘an Invalid Officer in the Honourable Companys’ Service’. He lists 3 female and 4 male slaves [leaving each of his children one slave], plus two male servants. And he still had some land but seemingly also debts, so his widow and children would not have been left with much. His son John was left property, which we know was successfully retained, as in 1863 some members of the family were still living there at Half Moon,[and six of his children were born there? – my copy lacks some info] .

Richard had married Mary Bazette in 1778 and there seems to be some mystery about her origins. For all the careful record keeping [births usually recorded when the child was baptised], Mary’s baptism certificate lists her mother as Elizabeth, not her mother Marys name. And her grandmother doesn’t mention Mary in her will. So was her parentage in doubt? A possible slave link?

Back to Samuel and his will of 1817. [see Appendix 2] which provides a fascinating insight into the life and family relationships of Samuel and his surroundings. And, in addition provides yet another source of unanswered questions about our family.

The context of the March 1817 will is that Samuel’s two youngest children, twins Martha [ MAMs mother], and Charlotte were 17. Neither were married but later that year Martha [our ancestor] was pregnant, and still not married.

In Samuel’s extensive March 1817 will are many references to named slaves [at least 20] who are bequeathed to his wife and children and it ends ‘My servants not given away in my will I request each to be allowed the choice of his or her master or mistress.’.

This will of March 3rd explicitly excludes two of his daughters Elisabeth and Martha from the bulk of his estate, each being left only £100, but significantly does not exclude Charlotte, Martha’s twin. All the other children including Charlotte were left houses, land, money and slaves and equal shares [always deducting the sums he had already given them]. The reason for Elisabeth only being given £100 and ‘she is not to share in any part of my estate with my other Children’ was because she ‘married against my consent’ one John Lam. Her daughter was however left £100.

So Elisabeth was being punished for going against her father’s wishes. But Martha? Why was she singled out? She was given the hope of coming into more of the estate, because in the event of her ‘marrying with my consent she is to share with my other children’. So it seems that at 17 Martha was known or suspected to be in a relationship with an ‘unsuitable’ man. Samuel had a fear obviously of his estate falling into the hands of ‘unsuitable’ men. Presumably at the time any assets of a wife were regarded as being the property of her husband.

Charlotte Martha’s twin was to share in the estate, with no mention of her losing any of it if she married ‘inappropriately’, and she was given two slaves. So she was not seen in March 1817 to be a problem, [nor had she already been given property or money earlier, which excluded some other members of the family from being fully acknowledged financially]

Samuel was however capable of softening his stand, because on the 18th April 1818 a year later, he added a codicil. One wonders what exactly had gone on in that year. By 18th April 1818 Martha had married her cousin John, presumably a man of whom her father Samuel approved, and so she was given a further £400 and 3 named slaves. So Martha was not after all likely to be too badly off when her father died.

Also in the codicil Elisabeth, the wife of the disapproved of Captain Lamb was now given a further £300.

When Martha and her cousin John were married on 4th March 1818 she was very pregnant, her first child Robert being born on 5th June 1818. It seems unlikely that John was Robert’s father, but intriguing speculations arise as to who was. And also what happened to Robert because records show only his birth, nothing subsequently.

When I visited the Oudtshoorn museum, Hilda Boshoff told me that there had been talk that the Edmeades’ were related to Napoleon. Glynis Snell’s research throws some light on where this story came from. There were several references to ‘the beautiful Miss Knipe’ [le Bouton de rose, or rosebud] on St Helena, and speculation that this was Charlotte. In 1816 there were references to Miss Knipe visiting Napoleon [why only one, if there were twins?].

Glynis Snell says ‘It has been claimed that the supposed liaison between ‘the Rosebud’ and Bonaparte resulted in an illegitimate child.’ There only seem to be three Knipe young women to whom this could have referred, the two most likely [because of their age] being Martha and Charlotte.

The truth will never be known but we can produce various scenarios.

If a Miss Knipe was visiting Napoleon in 1816 it seems more likely to have been Martha who was disapproved of by her father, than Charlotte[ unless her father knew nothing of her visits]. Feelings against the French ran high, and in 1817 Charlotte was in her father’s good books whereas Martha was not. Martha certainly seems to have been ‘visiting’ someone because later in 1817 she was pregnant. So who was Robert’s father? Napoleon?

Samuel, MAM’s father died in 1818 and in July 1819 his widow Amelia/Emilia had a trip to England. Did Charlotte her one unmarried daughter accompany her, before returning to the island for her marriage in June 1820?. It has been suggested that Charlotte [le bouton rose?] perhaps had a child [Napoleon’s] whilst away from the island? Or did Amelia, Martha’s mother take Martha’s son Robert with her to leave him somewhere in Europe? Apart from being born there are no further records of him. Who was Robert’s father? It seems unlikely that it was John, Martha’s husband.

It would please all the Edmeades in the family who hope for prestigious connections to think that our ancestor Mary Ann Margaret had a half brother who was the child of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Another intriguing issue from the Snell research is that of Charlotte’s husband’s parentage. Her husband Daniel Hamilton was born before his father married Charlotte Bagley in 1799, one of three such children. ‘Daniel, son to Sergeant D Hamilton and Ann [free] born ca 1796, baptised 20 Nov 1796’. This suggests that his mother was of black, or Asian slave descent. [not Chinese as they arrived later]. Baz had denied that there were relationships across colour lines which seems an unlikely assumption. But this shows that such relationships were officially recognised.

John Bazette and Martha had 11 children including Robert. [SEE APPENDIX 4] of which our ancestor Mary Ann Margaret {MAM] was their third, born in 1821 [in time for her to be fathered also by Napoleon?].

Mary Ann Margaret {MAM} married William Penville Edmeades from England in 1836, aged only 14. And they left St Helena. Some time between 1838 and 1841 the couple with their first son George Mason, left St Helena for South Africa. [It seems likely that it would have been 1838 or soon after because this was when it was said so many young people did leave.]

MP March 2012

Every family history gets interesting when a black sheep is discovered. Our Edmeades family delvings have not yet uncovered one. But they have uncovered mysteries and raised unanswered questions, questions to which it seems unlikely to get answers. What is surprising is how much the various family members have managed to unearth – about the Knipes in St Helena, going back to 1660 or 70, the du Preezs going back as far as 1688 to Europe, and the Mortimers and Haigs in Yorkshire going back to before 1865.

It is interesting that on the whole we know more about members of the family who didn’t start life in the UK than about William Penville Edmeades, who did start life in the UK, where there are many sources of quite reliable information on ancestors.

William Penville [or Penvil] the first English born Edmeades to settle in South Africa, remains something of a mystery in spite of various members of the family researching his possible origins. We could call this ‘The hunt for William Penville Edmeades, the Edmeades pimpernel’ – not scarlet or as colourful, but still very elusive. The results of the researches of family members are reproduced in full in Appendix 5 in order that others following do not simply reinvent the wheel.

Perhaps the one indisputable fact in all this is that the Edmeades family were a well known firm of papermakers in Maidstone called Edmeades and Pine. And there are still Edmeades descendents living in Kent at Nurstead Manor in Meopham now a conference centre.

Beyond that is supposition about William Penvil because although we have a birthdate and place for him one possibility is that he simply made them up when he was marrying Mary Ann Margaret [MAM] Knipe in St Helen in 1836.

The facts as presented by William Penvil [or Penville] Edmeades when he married, were that he was born in England, at Maidstone on 10th April 1810.

And we know from St Helena records that in 1836 William Penville was in St Helena, marrying MAM Knipe, aged 14 or 15. He was reportedly 26 years old. And we know that by 1841 [ aged 31?] he was in South Africa with her and their first child.

We have various possible versions of ‘the Edmeades pimpernel’s’ early years in England.

1] According to one family tradition, William Penville ran off to sea rather than following the vocation chosen by his family. A version of this, from Ian Edmeades’ father some seventy years ago, was that William’s father wanted him to be ‘a man of the cloth’ and to escape this he left home. The Edmeades being involved in East Indian trade, St Helena figured in this story.

2] Jane had another source of possible information on our elusive ancestor. There was a mention of a William Edmeades as a child on the Pauper’s List from Maidstone. Could this have been the same William who had been in trouble ‘for being a kind of early 1800s street child’? Was he perhaps the son of an unmarried Edmeades woman thrown out for her indiscretion?

3] Jane has now provided another possible scenario which is that William was not an Edmeades at all, but simply adopted the name of a well known Kent family when he got to St Helena. This one, if true, has particular irony. Many of us are interested in and researching ‘the Edmeades’ family. Is it possible that none of us are actually descended from the Edmeades’s? What are we?

Whatever the truth of William Penville’s origins in England we don’t know when, how or why he went to St Helena. All we know is that he was there in 1836.

Perhaps we might find out more about his origins if it were discovered that the Edmeades family in Kent was baptised privately not in public. This is because for information before reliable census records in 1841 public baptismal records were the best source of information on people’s births.

But meanwhile there have been various suppositions. Research has shown that he was not a cadet in the East India Company or in the armed forces which could have taken him to St Helena.

One suggestion was that he was a sailor, and jumped ship at St Helena. This could fit with the idea that he was a child pauper who might have stowed away or joined a ship. [But I think someone researched the crew lists of ships and did not find him?].

Another suggestion was that William possibly went to St Helena because there was already a relative there. It has been suggested that a William Edmeades [born 1803] was recorded as living on the island [baz], and family legend says that there was an Edmeades, Captain William in the force that was guarding Napoleon on the island in 1806[Mur]. If these are true, perhaps ‘our pimpernel’ heard of and was influenced by this.

So the family may after all have a black sheep but one who slipped through official records, so we will never know. We have to be content with a mystery.

MP Mar 2012

The Edmeades I grew up knowing about were The Aunts, my maternal grandmother’s sisters, a legendary group of Edmeades women who lived in Oudtshoorn. Their brother Leach and his family were the other Edmeades we knew. What we were told was that part of the Edmeades family had been very wealthy, and one of the heritage houses in Oudtshoorn was an Edmeades one, but not alas our branch. The ostrich feather trade had provided great prosperity during its boom periods. But in my lifetime the Edmeades Aunts were reduced to genteel poverty. They were the survivors of the seven girls of their generation, my grandmother, their eldest sister Elisabeth Catherine having died long before. So it was the four of these younger ones – Mary, Ethel, Rene and Edie who were ‘The Aunts’ to all of us.

But they were the second generation of Edmeades in South Africa, [and descendents also of much earlier arrivals, the du Preez].

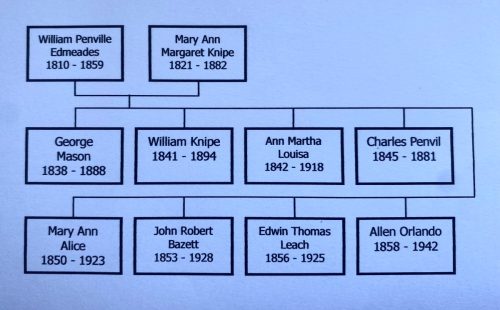

The Edmeades story in South Africa starts some time between 1838 and 1841 when Mary Anne Margaret [MAM] [nee Knipe] and William Penville Edmeades arrived from St Helena in South Africa with their first child, George Mason. We know little of those early years. But because economic conditions in St Helena at the time were deteriorating it seems likely that the young couple had little money, that they arrived, in current parlance as ‘economic migrants’.

It is also likely that they went to South Africa because the British government was offering incentives to people to emigrate in order to reduce the population of St Helena, and increase that of whites in South Africa.

We know that MAM was not the only Knipe to end up in South Africa. Her older sister Amelia married James Anderson in Cape Town on 10th December 1839.[Jane]. And her cousin Douglas Mortimer Hamilton [son of her mother’s twin Charlotte] was also in South Africa, dying there in 1900.

The family possibly landed in Mossel Bay as that is where they lived for some years. There William Penville worked as a painter before settling on the farm Zuurflakte.

However Jane discovered an application from W Edmeades in 1842 for ‘permission to retail liquor’. So he must have been running a store of some kind by this time, perhaps in parallel.

However by 1853 the family had moved to Oudtshoorn, onto the farm Zeekoegat. [This was said by Hilda of Oudtshoorn Museum to be a large farm half way to Calitzdorp on the banks of the Oliphants river.]

There in 1859 William Penville died aged 49 leaving a widow and eight children. The most we know about him at this stage is that his widow MAM and children later paid for a window in the new St Judes church in Oudtshoorn to commemorate him.

This window was given in a period when Oudtshoorn was developing fast. From the leaflet in the church we know that the original Oudtshoorn was 3km south, founded only in 1847, becoming a municipality 40 years later, just as the family fortunes disappeared. In this small settlement there was talk in the 1850s of building churches for the NG and RC congregation, and by 1859 for the Anglicans [of whom there were at that stage only 17 men, with only two owning property]. It was in this year 1859 that many of the Edmeades were baptised, presumably by a visiting clergyman.

Bishop Gray had consecrated four churches in the region in 1855, including that at Knysna [our Mortimer great great grandfather’s church?]. Ground for the Anglican church in Oudtshoorn was registered in 1860, but there were difficulties raising the money locally, and it was finally consecrated only on 26 September 1863. It was enlarged over time and it must have been one of these periods when the family paid, in 1880 for the window dedicated to William Penville.

By 1870 Oudtshoorn must have been transformed by the ostrich feather boom.

So William Penville died in 1859 apparently having no part in the Edmeades 25 year expansion in and around Oudtshoorn, as Oudtshoorn itself grew from a small settlement to an important commercial centre. From then on until 1886 when bankruptcy ended it all, the Edmeades’ were an important, indeed a key part of Oudtshoorn’s growth. And this success [and finally failure] were driven by MAM and William Penvilles first child, George Mason, born in St Helena and brought to South Africa as a very young child.

So where did William Penville’s death in 1859 left MAM , aged 37 a widow with eight children, the youngest Allen only a baby?. Only George Mason and William Knipe [the latter aged 18] could have been said to be adults. Ann, the next was 17, Charles Penville 14, Mary Ann 8 or 9, John 5 or 6 and Edwin only 3.

MAM seems to have been a remarkable woman, although we know little of her as a person, or of her life. She had probably grown up in reasonably comfortable circumstances in St Helena, come to South Africa before she was 20, already married with a child and probably in poverty. Then after perhaps establishing a relatively comfortable life on the farm she was left to cope on her own with young children. So once again she managed with presumably few resources. No wonder she has come down in history as a woman to be proud of, as witness the following tribute in a preamble to the Edmeades family tree [author uncertain].:

‘When taken into account that she was only 37 when her husband died, stranded in a new country with 8 children, the eldest not yet 21 years and the youngest not yet 9 months, then her descendants can be proud to have her as an ancestor .Comparing the names of the first generation to the surnames of the Civil Servants of St Helena, in 1785 it is clear that she came from a well-educated family. When the history of her children is researched, it is also clear that her upbringing was passed on to her children. It is with pride that the author of this web page claims to be a descendant of such a remarkable woman.’

I have long been aware of being part of a family of strong women, who have survived many hardships, often being the sole or main breadwinner. Since learning of MAM, it seems these strengths and values can be traced back many generations.

But there are others, her two eldest sons, and perhaps her daughter Ann, who must have played an important part in keeping the family going during the difficult years after their father’s death when the other children were young. At least two of these youngsters John, and particularly Edwin had the upbringing, self confidence and education to enable them later to become successful business men.

But there are many questions about how the family survived both before and after the death of WP. For instance, education. Did the children go to school, and if so where and when? Perhaps MAM educated the children herself? In which case what education had she had in St Helena? The most likely answer would be home education with a governess. But we don’t know. There seems to have been a strong emphasis in the family on education, even for girls, which seems most likely to have come from MAM. In South Africa there were few formal English language education opportunities available for girls in Oudtshoorn even when Gwenda was at school in the 20th century. [She had to be sent to school in George]. On 30th July 1879 the Courant tells us that a school for girls opened ‘Jonge-Jufvrouwen’ at the cost of £48 pa. Was this the first school for girls in the town?

There was obviously an English language school for boys by 1886 because AB Mortimer got a school prize there in December 1886.

How long MAM stayed on the farm Zeekoegat is not known. Her eldest son George Mason was making a living in Oudtshoorn even before his father’s death. William Knipe her second was also working in Oudtshoorn, and then moved away to his wife’s family in Humansdorp. Ann, the third married. Charles probably soon got absorbed into the family businesses. So either MAM ran the farm, or it was sold and she moved, presumably into town.

Mary Ann Margaret Edmeades died aged 59 in 1882 in Oudtshoorn, living at the time with her second son William Knipe and his wife Maria Jacoba [our great grandparents], not as one might have expected with her successful eldest son GM or her married daughter Ann. She left an estate of nearly £500, having been reportedly living on the interest. [baz] [This sounds like a not inconsiderable amount] Did this money come from property on St Helena, or from the Edmeades family business, or from selling the farm?

The Oudtshoorn Courant’s [5/9/1882] notice of her death gave her age as 59 years, 11 months and 25 days. She could not therefore be described as being 60! Four sons, George, William, John, Edwin, and grandsons followed the hearse [where was Allan?], followed by daughters, daughters in law and grand daughter in vehicles, and about 500 members of the general public. Nothing more about her or her life [she was after all only a woman!]. She was taken to the English Church, then to the English Church Cemetery.

This lack of more information about MAM [who was described by her descendents as a remarkable woman] highlights one of the issues about biographies of people long dead. Men may appear in public documents as landowners, owners of businesses or employees, members of clubs or committees, law suits, and so on – the public world. The official and business world, which was what was reported on was a man’s world. Women did not have official positions and the local newspaper did not report on women’s activities [until later Great Aunts Mary and Rene had items about them in the paper].

Women are known about through the stories of home life, or from official recordings when they are born, get married, give birth, and die. In the case of the Edmeades we don’t have letters or diaries, so often a rich source of information for biographers. We don’t for instance know what MAM’s daughter Ann’s role was in keeping the farm and family going after her father’s death. Ann married George Kent, [described in parish? records as a saddlemaker in 1864 when they married]. Perhaps they were not affluent enough to help support the rest of the family?.

What we do know is that George Mason [GM], MAM’s eldest son, whilst described as living at Zeekoeigat was also described as a kleinhandelaar, so at the age of 17 he had already started a retail business of some sort. And by 1858 GM was in Oudtshoorn, described as a painter [verf en plak] like his father before him. So it seems that from even before his father’s death the teenage George Mason was earning money, and soon started building up the family’s businesses and therefore presumably the wherewithal for his mother and the younger ones to live.

MP Mar 2012

As we move on to the period after 1860 the ‘Golden Age’ of the Edmeades’ in Oudtshoorn, the person that takes centre stage is WP and MAMs eldest son George Mason [GM]. This is partly because the family businesses were in his name. But also because he seems in many ways to be such a dominant although not necessarily a likeable person.

When I started my research in the Oudtshoorn museum I was intent on finding out more about my great grandfather William Knipe, and my grandmother’s generation. But after my few days in the museum I became so intrigued by this man, whose existence before then I was not even aware of, that I sat and drafted a chronology of as much as I had found out about him, mainly from the local newspapers. [see Appendix 7]. This was partly of course because as the GM of GM Edmeades and Bros he was much more in the news than the others. But I learned how biographers can start building up a picture of their subject even if long dead just from a collection of documents and reminiscences – a picture possibly incorrect, but who can dispute the suppositions more than a hundred years later?

And as I built up a picture of George Mason, so I found it increasingly difficult to do so for his brother William Knipe, who I really wanted to learn more about. William Knipe, his slightly younger brother, my great grandfather remains, like his father William Penville a somewhat unknown figure, perhaps because of being in his brother’s shadow.

So the story of the growth of the Edmeades businesses in Oudtshoorn until 1886, and therefore the story of William Knipe will be centred mainly around that of his brother George Mason.

What follows are many details, gleaned mainly from the newspapers of the time. But it is through the detail that we can build up a vivid picture of how the Edmeades’ businesses in Oudtshoorn grew and grew, largely probably through George and his determination to succeed.

When William Penville [George’s father] died in 1859 WK our ancestor, the second eldest was reportedly running the farm where presumably the rest of the family lived, whilst 21 years old George’s occupation was said to be that of a painter [like his father] in Oudtshoorn. He had started his entrepreneurial activities before this because in 1855, then aged 17 he was described as being a kleinhandelaar, so had already started a retail business of some sort. And three years later in 1858 GM was described as a painter [verf en plak] the pastorie, van der Riet’s property on the corner of van der Riet and Baron van Reede Street.

To put the development of the Edmeades businesses into context one needs to know something of Oudtshoorn and how it was developing. It was in 1855 that the village/settlement had its first magistrate and the beginnings of a municipality. At that stage the records say there were only 30 houses, and 40 huts, and the population consisted of 200 whites and 300 coloureds. It was small!. But perhaps the 200 whites recorded were only the adult males living in the area. In 1858 a schoolroom was established. And in 1859 the town/village had both a drought and a ‘depressed economy’

So this is the background to the Edmeades businesses’ expansion, with George reported as beginning his own business on erf 175 in 1862. And he must have been very successful because in 1863 he gave the ground for a cricket club and became one of the first commissioners of the newly established Dorpsraad or municipality [which he remained until the 1880s], and of the Afdelings [Divisional] Raad. And at some stage he became a Justice of the Peace.

In 1864 he is described as a storekeeper, and by 1865 had a smidswinkel and wamakery.

This was a year when ‘serious poverty’ was reported in the newspaper. In 1866 there was reported to be a drought, followed in 1869 by floods. But the drought and floods do not seem to have affected GMs developing business. It grew so that on 28th October 1869 the George Advertiser had an advertisement for George Edmeades, General dealer, wagon and cart builder, tanner, butcher, and baker. And also Cart and horses to hire. And in 1871 he was advertising for sale a huge range of products –wagons, carts, fruit, corn, oats, barley etc in the Beaufort Courier. On 20th September1872 he claimed in an advertisement that George Edmeades of Oudtshoorn had ‘always on hand and which he offers for sale at low prices ready made ox-wagons and carts’ and also that he will take sheep in exchange.

We don’t know who was running the farm. Anne was married. Perhaps it was Charles, or perhaps MAM on her own, or perhaps they had sold it and left?

The heyday of the Oudtshoorn first ostrich boom was said to have been between 1875 and 1880. At one stage a pair of ostriches was reportedly sold for £1,000!!!

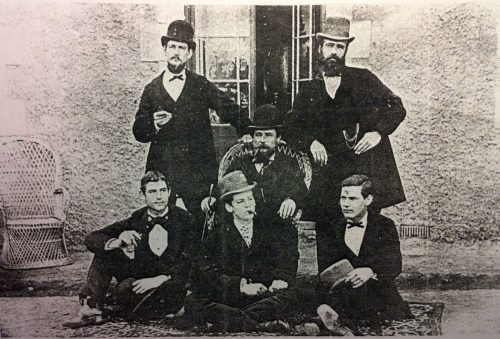

The photo of the Edmeades men around 1875 shows them in poses befitting members of a leading Oudtshoorn family, all looking very debonair, clutching cigars, [but with someone spotting that John appeared to have a hole in the sole of his shoe.!]

The Edmeades Brothers – c1875

George Mason sitting in the centre, Charles and William standing left and right. And in front from left to right Edwin Allen and Johnny.

This picture contrasts with my memories of pictures of Edmeades men in sporting teams in Oudtshoorn which I [and Penny later] saw when we, during our university vacations worked in the Johannesburg library in the 1950’s laboriously writing out by hand cards for each human in each photograph from thousands of different sources. This in order to create a photo library. [hopefully this still exists and should be researched]. Both our memories were that we had ancestors who looked extremely tough and somewhat gorilla like. But perhaps these were pictures of rugby teams????

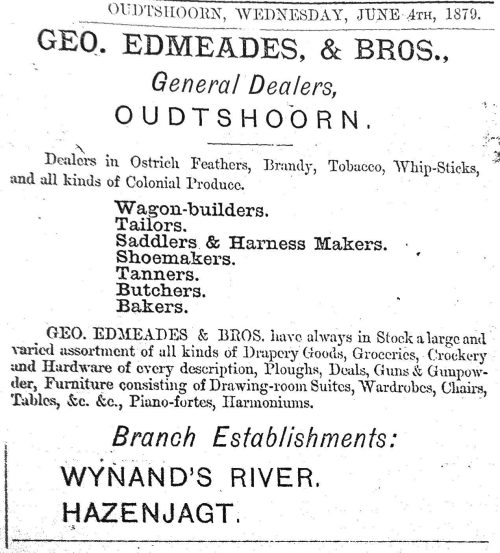

The museum has copies of the Oudtshoorn Courant from 1879 [Vol 1 No 2]. This seemed to appear twice weekly and much of the time in parallel Dutch/Afrikaans and English identical items. In these there are prominent advertisements on page one for George’s businesses, which from some time after 1872 and until 1883 was described as George Edmeades and Brothers. We don’t know but it seems likely that the business included all of them once they were adult. [Charles was 15 in 1860, John 15 in 1868, and Edwin 15 in 1871].

The business seems to have expanded in all directions – with branches open in surrounding areas, and providing an ever widening range of services and products. There seems nothing that anyone in Oudtshoorn or surrounds might have required that the Edmeades businesses could not or did not supply.

There were branches in Wynands River, Hazenjagt, Styldrift, Schoemans dorp.

To the above businesses are added [in 1879] auctioneering, with Ford. This seems to be a venture of George alone although it is the GM and Brothers’ stores that in June are auctioning sheep, goats, cart and riding horses and mares, and plots in the village, and ‘whatever else will be offered for sale that day’ and for which ‘liberal credit will be given’.

On 12 May 1880, according to the museum’s Waenmakers document, a tender was granted ‘om die afdelingsraad van skotskarre teen ?35 te voorsien’ [whatever that may mean – a contract to provide the district authority with their carts or carriages?]

In March 1881 George applied for wine and spirit licenses to keep a hotel with ‘privileges’[sic] on erf no 114 Oudtshoorn. [successful?] And by 1883 they were agents for Donald-Currie Steamship Company. There seemed to be no end to George’s ambitions and business expansion.

But in 1883 things started to fall apart. By November the family partnership was dissolved. We don’t know who the partners would have been, but by then all the family were adults. It is possible that the death of their mother MAM in September 1882 had something to do with the decision to break up the business, as also the death of brother Charles of typhoid the previous year. Charles was described by Baz as having a gentle nature, and possibly being the peacemaker, [but who also was divorced in 1879 by his wife, probably a rare event].

Was the break up of the business a result of a change in the economy in Oudtshoorn? The first ostrich feather boom ended in the 1880s, [followed later in the 1900’s by another boom] .The website records that it was in 1885 that there was a sudden slump because of overproduction [of ostriches and feathers] and severe flooding. But the Edmeades problems had started before this.

What seems perhaps most likely is a combination of an economic downturn and some [perhaps all? i.e. including WK] of the family no longer wanting to work with or for GM. And with their mother and Charlie no longer around to keep the peace Baz says that the three youngest moved out of the firm – John aged 30, Edwin aged 27 and Allen aged 25.

[Was Allen in the business? He was not at his mother’s funeral in 1882, perhaps he was already in the Transvaal].

Ian in a letter to Lyn [15/7/02] says that his father Laurie’s version of the story was that at the time of one of Oudtshoorn’s depressions many farmers had to dispose of their properties and GM bought them. The bank manager required him to consult with the bank before buying more properties and his attitude was ‘who was the bank manager to dictate to him’ and he continued as before and the bank foreclosed. This resulted in a cash flow problem and the brothers lost their fortunes while the bank made a fortune.’ He said also that Edwin was not affected as he was not in the partnership.

Piecing all this together it seems likely that in 1883 WK was the only brother left in the business with GM. Why he did not leave with the others is not known. Was he afraid of yet again failing on his own [he had had one bankruptcy]? Were his affairs more tied up with GM than were those of the others? Did he, like GM perhaps think that the good times would last forever and with a large family to provide for he was better off sticking it out with GM? Or was it just that none of the others wanted to work with GM? Whatever, two at least of the younger three men [John and Edwin], made very successful business careers on their own. And poor old WK was involved in the final chapter of the end of the business and of his and GMs prosperity only a few years later.

The Courant records it all [apart from the personal relationships]. On 18th September 1883 it reported an auction ‘om van sy oortollige waens and karre ontslae te raak.’ George got £105 for a new wagon, £60 for a kaapse kar, £35 for a phaeton, and Scots cars raised £25 each.

And on the 5th November 1883 ‘All accounts owing to the firm in Oudtshoorn, as well as the branches viz Hazenjagt, Wynands River and Schoemansdorp must be settled as promptly as possible’, followed on the 13th by a big notice on the front page ‘George Edmeades and Brothers previous to a dissolution of partnership are now selling off in the different departments their general and varied stock at greatly reduced prices.’

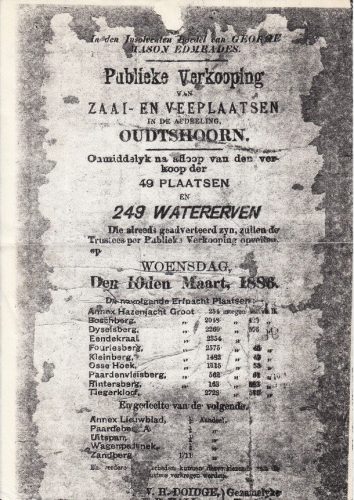

George tried to continue in 1884 as George Edmeades and Company Auctioneers. But in March 1886 the first sales of lands of GMs large but insolvent estate were advertised.

This consisted of 10 properties and parts of another 5. The copy of the notice I have is unclear, but the numbers of morgen are clear [how big is a morgen?] They range from 2729 morgen [five being over 2000 morgen], to one of only 163 morgen.

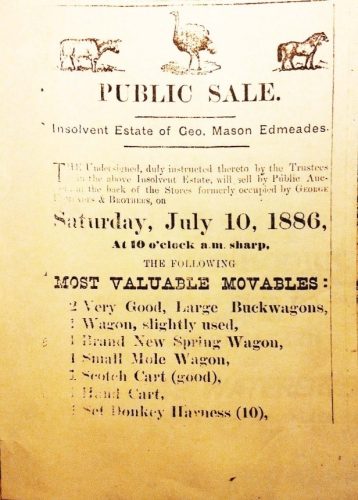

And in July 1886 another huge front page advertisement of the public sale of moveables and livestock from his insolvent estate. These seem slightly sad considering the not so distant past. There are 7 items – 2 very good, large buckwagons; 1 wagon slightly used; 1 brand new spring wagon; 1 small mole wagon; 1 scotch cart [good]; 1 hand cart; 1 set donkey harness

At the time of GMs bankruptcy he reputedly owned almost the whole of the west bank [or is the Wesbank, a bank?], and large parts of Oudtshoorn [Courant and Waenmakers 6/1/86]. His funeral write up in 1888 says that the Divisional Council valued his landed property at over £100 000, including many of the best farms in the division, more than one half of the erven in this town besides properties in other places …had he realised his properties some seven or eight years ago, he could have retired a wealthy man, but owing to the severe depression in trade that set in about that time, and has continued since, he sustained severe losses.’

There is a family story mentioning the sum of about £350,000, possibly to do with the banks’ assets that suggests that perhaps a quarter of the banks’ [or bank’s?] assets had been invested in him?

Coincidentally, on the web is the story of the developing prosperity of quite another family at this time. Wilf Sanders opened his first store in Oudtshoorn in 1885 at 33 St Johns Street on the corner of St Georges Street, doing well enough to buy the building in 1887 for £600, with a mortgage. And as the Jewish community in Oudtshoorn grew and flourished a decision was taken in 1886 to build a synagogue, with the Foundation Stone being laid in 1888.

So whilst one family’s prosperity grew the Edmeades tale of decline continued. In February 1887 there is a report that ‘the late residence of’ George Mason Edmeades, corner of Church and Queen Street is being improved.’ Another storey was being built and the current owners were planning a retail and wholesale store. What a downfall!

It seems not unexpected that George Mason died in 1888. He had had an amazing career during which his businesses reputedly owned most of Oudtshoorn, ending with all apparently lost, He was a quite extraordinary man, and died aged 49 on the 4th January 1888 in Oudtshoorn, after ‘lingering for the last 6 or 7 months, suffering at times most excruciating pains.’ The funeral took place in the English Church where at the end of the service ‘by special desire of the family’ there was a presentation in the Dutch language, as many mourners were not able to follow the English service. He was interred in the Dutch Church cemetery in the family vault.

His funeral notice is long, as befits one of Oudtshoorn’s leading business men. ‘…he wielded a personal influence in this district that will probably never again fall to the lot of anyone else’, said the minister at the funeral. ‘There is not a man, woman or child in the division of Oudtshoorn that has not heard the name of GME’… ‘having a natural bent for business and speculation… unbounded energy, dauntless will, and indefatigable industry… Although GM had his faults and some enemies… even those who were not in sympathy with him could not but express admiration for the gifts with which nature had endowed him, and this admiration found expression in the kindly feeling that prompted the unanimous act of esteem shown by all his fellow-townsmen in closing their respective stores and offices on the afternoon of the funeral.’ As the members of the Athletic Club were starting their cricket match and heard of his death ‘they unanimously agreed not to proceed with the game’. ‘He was a former President, and proprietor of the field which he provided free of charge’.

‘Many can testify to his assistance when in distress, and never was he known to refuse aid in a good cause. He subscribed £500 towards the first class undenominational school for boys… If he had chosen to stand for parliament he would have been placed at the head of the poll against all comers.’

Not the warmest description of a much loved man. The one positive thing of him as a person was a reference to the fact that in the drought of 1866 he had fed a large number of poor starving people

The Museum archivist has collected material on the Oudtshoorn wagon makers, and with reason. When one considers the importance of wagons and carts in the 19th century, one realises that these must have been the Henry Fords of their day. Think of the state of the roads or tracks. Think of the distances which people seemed to cover. Think of the damage that must have been done to any vehicle used in these conditions. And then think of the money to be made building and repairing these vehicles. No wonder GM and the family business became affluent. And add to this GMs entrepreneurial instincts and capacity. He spotted opportunities and grabbed them. But his business acumen stopped short of realising that the good times could not last forever. When there was a downturn and people were selling off farms and properties cheaply he assumed that the good times would return, and apparently took the opportunity to buy up properties. But in order to do so he had to borrow. And the bank or banks from whom he borrowed, perhaps having a sounder view of the financial future, became alarmed at the amount he owed them, and foreclosed. This was obviously, within the family anecdotes, translated into the banks behaving unfairly and unjustifiably, and making a lot of money as a result. One wonders whether had GM been an easier character, those he was borrowing from would have continued to lend. But whatever the banking system that day, to issue a final ultimatum to someone who owned reputedly much of the town must have been a decision not taken lightly. Before the end, in 1886 one can only imagine many meetings to try and reach a mutually satisfactory decision. And in the end, GM determinedly not giving in, the bank managers having to decide to take the final decision, and call in their debts, with all the consequences for the town that would follow.

And perhaps by then there were others ready to pounce? Others who had not overstretched their resources, and who therefore could benefit? One would need to know much more about what was happening in the economy locally and in Oudtshoorn particularly to know what happened in the town as a result of the banks’ foreclosure of GMs business. It seems significant for instance that the following year, 1887 GMs property in a prime position was being developed by whoever bought it.

So in the end was it GMs arrogance that finished him, he who had built up a vast business which had kept a whole family? And where was WK, his brother in all this? Did he believe in GM as the omnipotent provider and man of good judgement? Or were his assets so tied up that even if he saw catastrophe ahead he saw no way out? Because in 1887, the year after GMs bankruptcy WK was [perhaps desperately?] borrowing in order to keep properties, some of which he presumably had thought were his anyway?

One can create a convincing story of George Mason as a single minded arrogant man, coping with children who in no way seemed able to help him or continue his business, and who were a constant worry. And whose slightly younger brother was still part of the business, but had no great business sense, who stuck to him for whatever reason, and for whom he possibly had not much regard. And faced with his three younger siblings walking out on him and his [or their] business partnership three years before his bankruptcy, precipitating a crisis. He could well have seen himself as a man wronged. And there would be no one around now who could dispute this version! – such is biography.

So what sort of a man was GM, apart from being an entrepreneur who finally overstretched himself? And where were the rest of the family and what were their roles during this extraordinary quarter century saga? We get glimpses of them in the newspaper from time to time. And there are family stories which give some clues to relationships.

His own personal family history is not a happy one. There are no descendants of his nine children. What we know suggests a disturbed or dysfunctional sounding family.

George had married Aletta Loock in 1860 when he was 22 [the family tree has no more information about her, her birth or death date.] He had been baptised that year as were the rest of the family. George and Aletta had nine children, of whom at least 4 died in childhood. Of those that are known to have survived, Mary Ann Margaret [Marion] died in 1937 aged 75 unmarried [I have a photo of her grave]. Edith Amelia another surviving daughter also didn’t marry. Charles Penvil [Tossie] was married and divorced with no children, and died aged 71. The line died out with these people’s deaths

Mental illness was a taboo subject, as we know from the fact that Milly Yates’ problems were kept secret from most people. But there are reports of several of GMs children having mental health problems. And the fact that the family tree has so little information on facts of their lives, or those of their mother’s suggests that much about them was covered up in the hopes that people would never know of their perceived shame. We don’t even have all their dates in an otherwise remarkably comprehensive Edmeades family tree. How much the mental illness in his family affected George we will never know. Neither do we know whether his reaction to it may have made things worse for the sufferers, by for instance putting people in asylums who might have been able to function in the community, given support. What we do have, however, are the Edmeades’ myths/anecdotes that all of these mental health problems were nothing to do with us, the Edmeades, but all to do with George’s wife and her family, the Loocks! – ‘not in our back yard’ such is the shame of mental illness! [baz]

So what do the Edmeades stories tell us of GMs family and their problems?

Charles Penvil [Tossie], George’s son, was reputedly a character. We have a photo of him on the staff of his uncle John’s firm.

Staff of Divine Hall & co c 1890 – Johnny Edmeades manager, and Tossie [GM’s son] far left front row:

From various sources, perhaps because it is a good story, I was told, or read about him being told never to set foot in the firm again. And so the next day he came in walking on his hands. Rev Beddy [1976] said he was brilliant at figures, though inclined to be moody and very eccentric.

Tossie’s sister, George’s daughter Edith, of whom there is a photo in the Oudtshoorn museum, was a beautiful woman and the first matron of the new Oudtshoorn hospital. She was born in 1868, so would have been around 30 when remembered by a very young member of the family. This was Henry Charles Edmeades [born 1896, a son of John R B Edmeades by his 2nd wife]. It was the opening of the Oudtshoorn hospital. ‘The Hospital came into being at the height of the Boer War and feelings were running high – pro-british and pro-boer and …… the Town council, the Divisional Council and or the hospital board changed’ whilst it was being built and ‘the name was changed at the last moment from ‘Public Hospital to Royal South Western Hospital. Cousin Edith was the first Matron and I have an idea that she lived in from the start. I well remember being dressed in a sailor suit with a big white starched collar which choked me to the point of suffocation and marched to the Hospital with the rest of the family to pay respects to Cousin Edith. We were taken to the Matron’s parlour’.