This is my attempt, written in 2023, at creating a picture of my father, a complex man. It is based on the various documents and snippets I have which were passed down from my mother, his wife, Murie, who presumably got them from him. And also drawing on my memories of him, of what I heard about him and of the stories I have built up based on all these. And of course, his writings. There are many gaps, and inevitably questions, so what follows is simply divided into specific dated periods.

Allon was a restless and driven man and ultimately a disappointed one.

We have his photo album, his version of much of his later life. Inevitably this presents one version of this man.

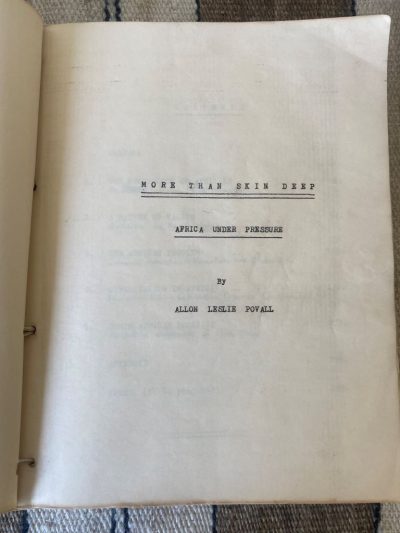

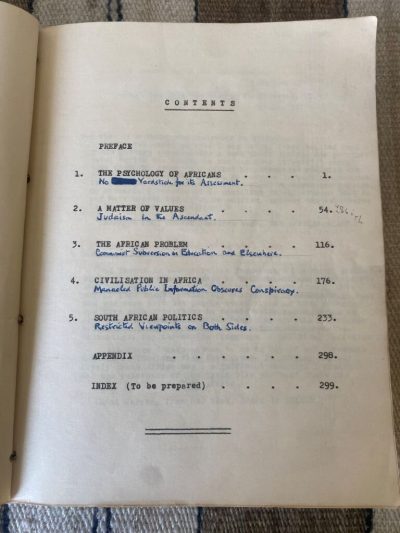

And there are other documents and notes about his life as well as the title and contents pages of one of the many books he wrote [not one of them ever published]. This particular manuscript was written in 1958 after he returned to South Africa, disappointed after 8 years in the UK trying to get his message to the world, both through writing books and giving lectures.

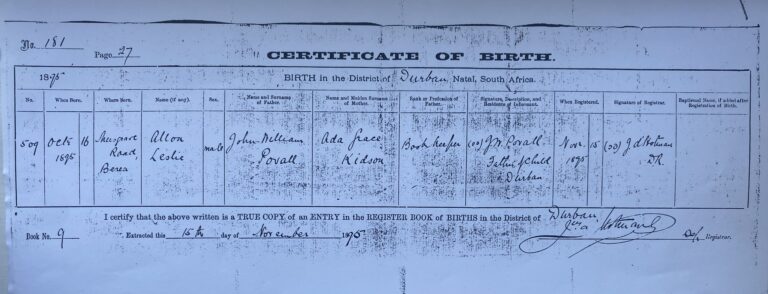

Born in 1895, an only child, Allon was, at the age of 14, told by his dying father that he should ‘save the world’. Much of his later life is clearly based on this. However, much earlier, there are episodes which suggest a great restlessness, an innate need for change and perhaps also challenge.

1913-1919

Doing well at school, Durban Boys High, he unexpectedly left in 1913 before taking his matric. This was probably to join the army for a secret operation somewhere which I have always understood to have been in another African country. It was the year before the outbreak of the 1914-18 war. Unfortunately the note about this operation, labelled by Murie as ‘top secret’, is lost. There are however various references to it in letters of recommendation.

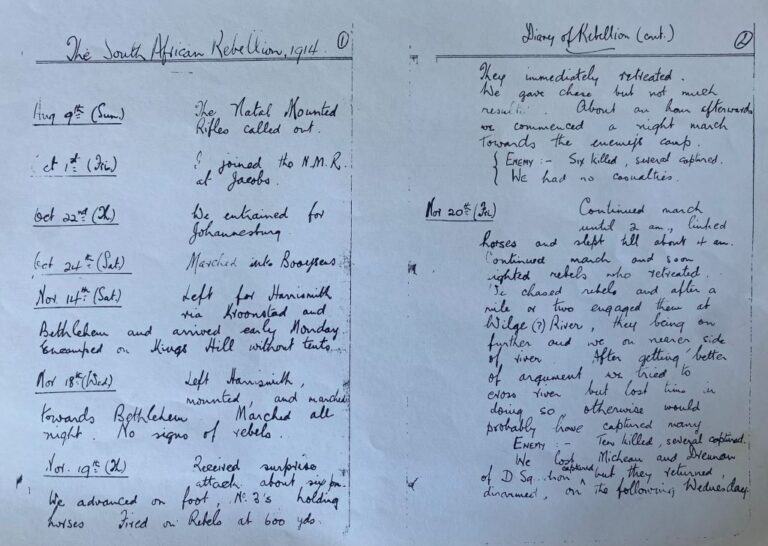

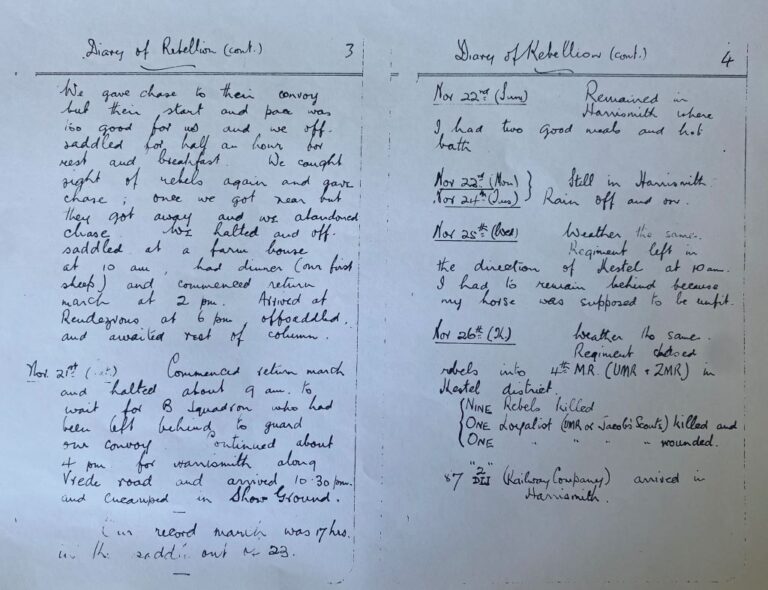

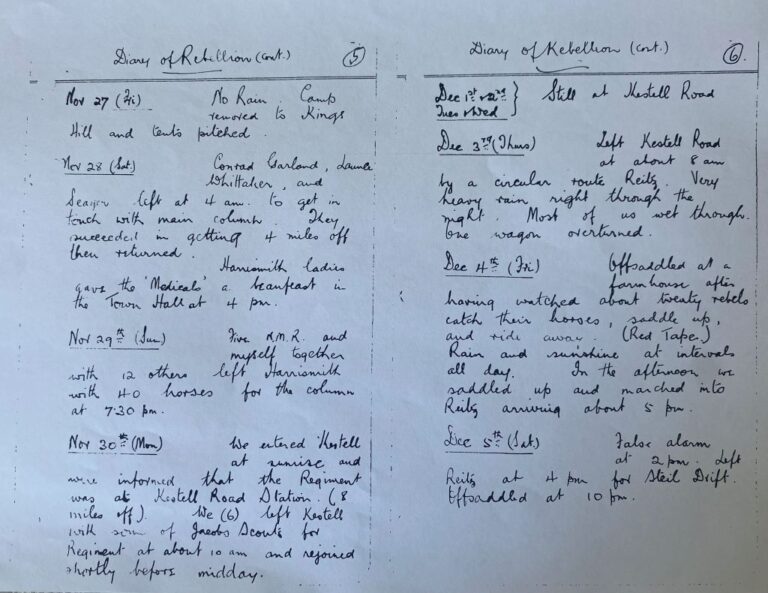

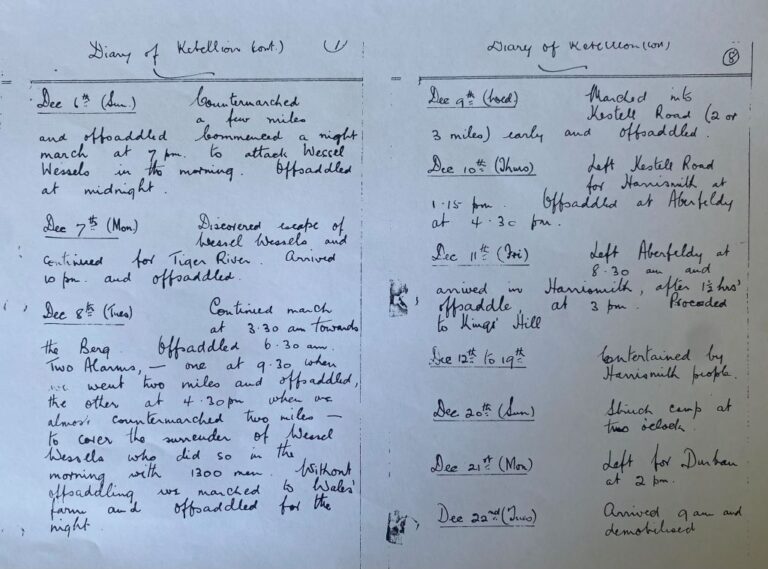

What follows here is his handwritten report on what he described as ‘The South African Rebellion, 1914’ and which covers his activities from August to December 1914

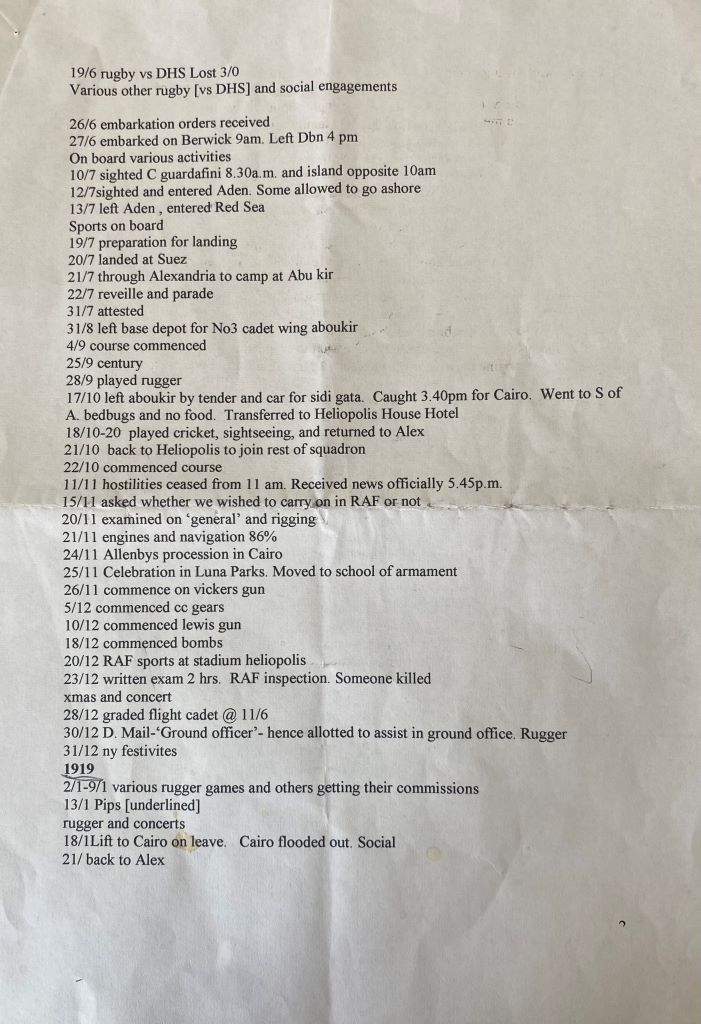

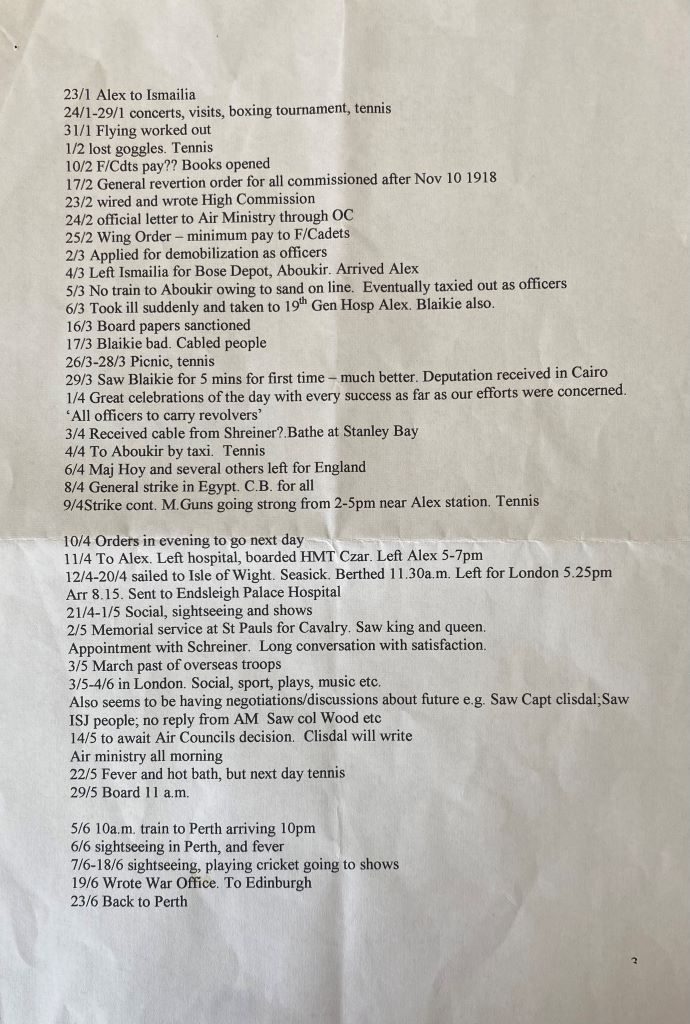

After this operation, he went and worked on a sugar plantation and didn’t join the Armed Forces again until 1918. In 1916 the ‘Number 3 school for Military Aeronautics’ was formed and the decision was taken to open pilot training schools in Egypt [Aboukir]. This seems to have been what attracted him back into the armed forces. His application to join was made in 1917 and he left for Egypt in June 1918, with his training beginning that September. It was while in training that the hostilities ceased and he was asked whether he wanted to continue in the RAF. He wanted to continue but was not automatically accepted and subsequently received a certificate, dated 4 March 1919, stating: ‘A CERTIFICATE FOR CADET WHO CEASES INSTRUCTION OWING TO CESSATION OF HOSTILITIES THROUGH NO FAULT OF HIS OWN’. He had done 35 minutes of flying instruction, plus other courses. In the end, he had to leave Cairo for the Isle of Wight on 12 April 1919 en route to London. Negotiations to be able to continue in the RAF continued in the UK, unsuccessfully for him, until, on 20 December 1919, he was forced to set sail for South Africa .

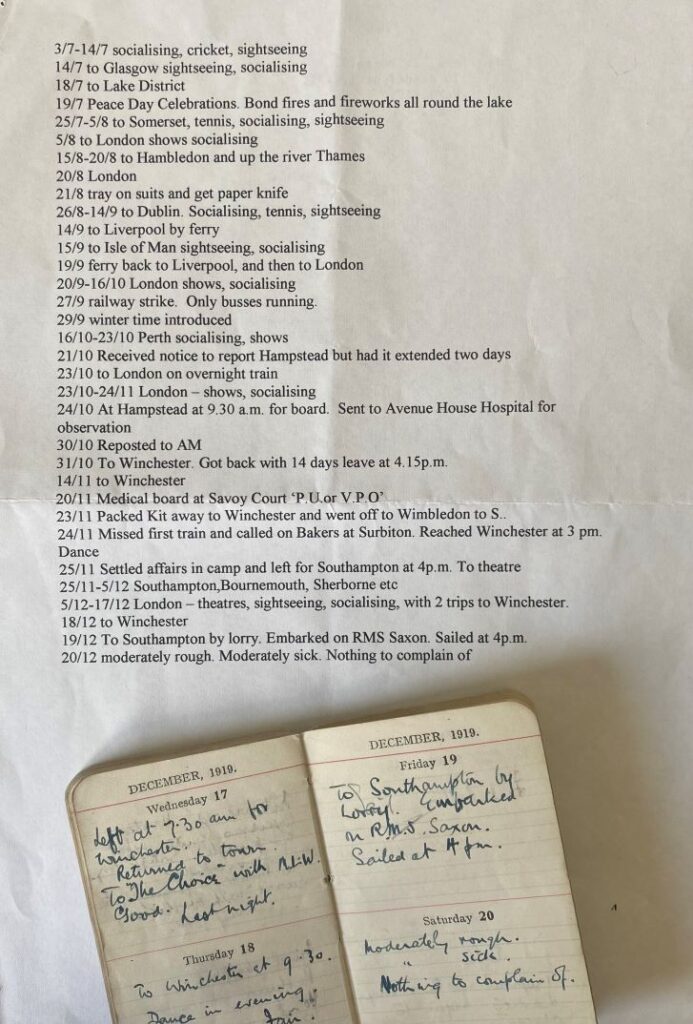

1917 – 1919

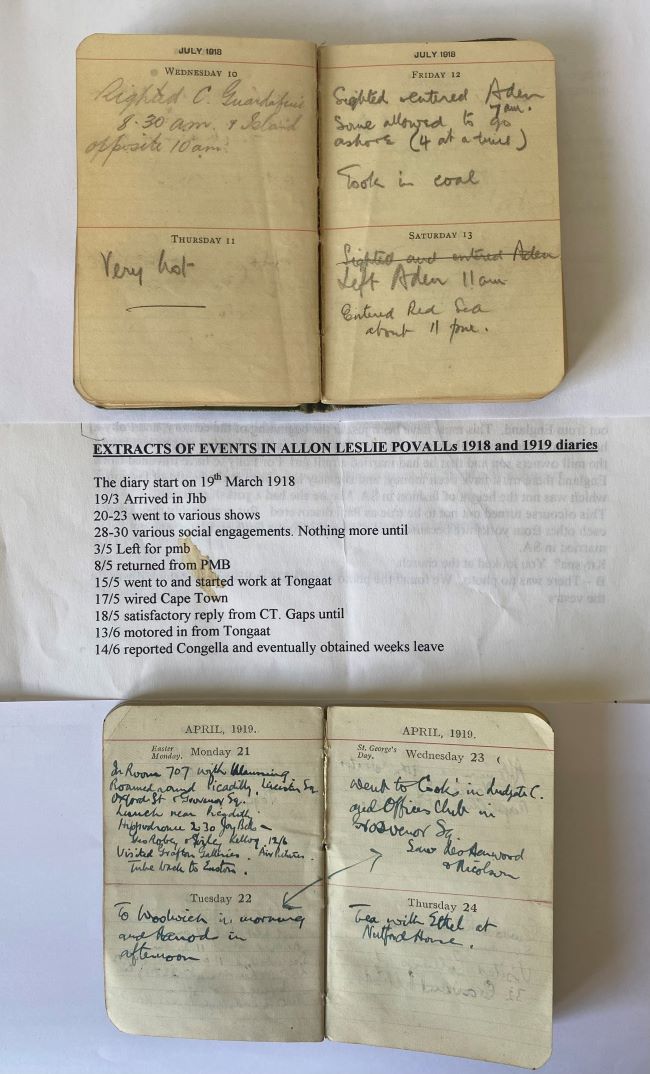

Summary of documents about him which I have mainly from two very small diaries:

After World War 1

As a returning WW1 soldier to South Africa, Allon was ‘given’ a farm outside Lydenburg. His knowledge of farming was only that of sugar cane farming in Natal. He had local ‘help’, presumably from people living on the site. He started in a tent with his record player, and also, I think, his piano. His presumably illiterate helper was often instructed to put on operatic records such as Celeste Aida.

One of his employees, ‘Neffies’, built one, and later 2, drystone wall rondavels [part of these still survive, so well built were they].

They were built at the top of the hill where Allon also created a field and tried to grow various crops. Down the hill, next to the river, was another field where he planted mango trees. With no funds to pump water from the river to either the bottom field or to the one at the top, he had little success. He was living in a way not dissimilar to the local inhabitants who, without the labourers he had, must have lived a very hand to mouth existence.

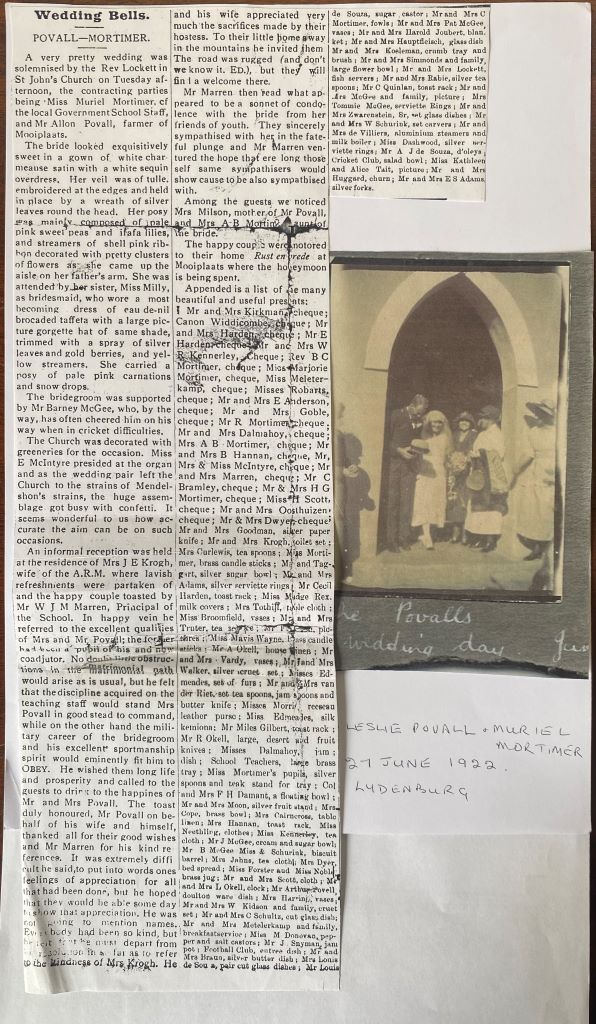

On his Harley Davidson, Allon would drive into Lydenburg and cause quite a stir amongst the small English speaking young community. Murie was teaching locally. He regularly joined her in the cinema where they played the necessary atmospheric music on silent films. In June 1922 they married and Murie joined him in his two rondavels, presumably with all their largely inappropriate wedding presents – more suitable for a settled couple in a house, rather than a hand to mouth existence in huts.

Murie continued teaching even when pregnant with Peggy, born in 1924. She commuted weekly, presumably on the back of his bike … and when his bike broke down, she merely walked along the river, not on the road, the many miles to town.

The Edmeades family history (chapter 2.4.1) details their challenging life in Lydenburg. With a drought, and probably his lack of interest in making a living there, their lives and those of their children and widowed mother were uprooted with a move to Johannesburg. There, he made a living working for a bill posting company, driving his truck home each evening.

In 1939, although he did not have to, he joined the forces again and once more ended up in Egypt. This time, Allon was in charge of a Cape Coloured regiment [see his album]. When he eventually returned to Johannesburg after the end of the war, he managed local cinemas until he left for England in December 1950.

My childhood memories are of him coming home from work and spending evenings on his card table, either writing or playing 2-pack patience. His handwritten texts were typed up often by my sister, Barbara. I always understood there was one book being written, but later we found several, all unpublished. I found his right wing, white supremacist views (as reflected on the contents’ page below) impossible to handle. None of the family wanted any copies. As a result, they were all destroyed apart from just one, which I kept simply as a record.

After he came back from the war, he never settled. His restless need to save the world meant that he felt he had to take his message to England and my mother allowed him to take his pension and do that. Because of this move, his mother, very reluctantly, had to move into an old age home and Murie, her two daughters who still lived at home, and the dog, Bimbo, all moved into a boarding house in Kensington.

HIS LIFE IN THE UK, 1951-1958

His album gives little information. He was based mainly in the Parkside Hotel on Seven Sisters Road, North London. From there he gave lectures on South Africa [as did his eldest daughter, Peggy]. Slides were provided and presumably South Africa House got requests from various schools and groups for his presentations.

Allon’s advertising brochure:

The Birmingham Mail published an article on a lecture given by Allon at Birmingham University to sixth formers in 1955:

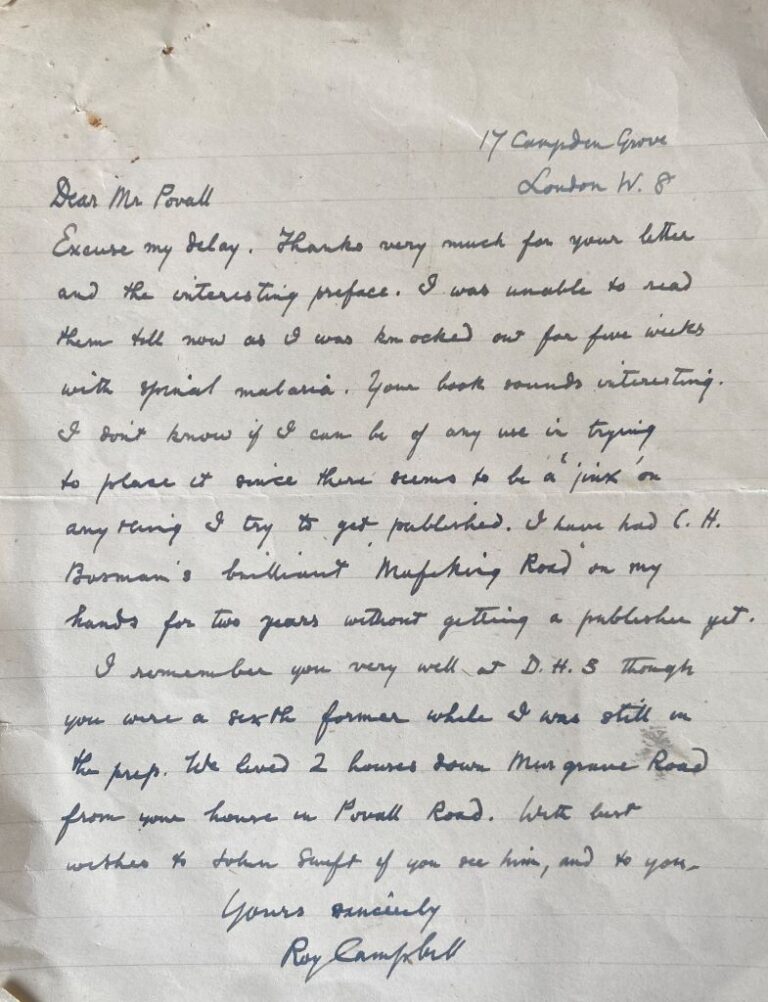

It did not all go according to plan. At some stage, he washed dishes in his hotel because he couldn’t pay his rent. All this went on while he was presumably trying to get his work published and get recognition, which included approaching the author, Roy Campbell.

His views on the superiority of the white man and of the Jewish conspiracy were held by right wing groups in the UK and he got involved with some of them. His books, although well written, and scrupulously researched, including the forged Protocols of the Elders of Zion, were never published.

After putting great pressure on his wife to join him in England, and not being successful, he retired to ‘manage’ a remote Welsh youth hostel, while he presumably continued writing. Then, in 1957, he returned to Johannesburg to his reluctant wife. He brought with him a gift for his wife and daughters, a roll of dark brown good quality woollen cloth, which I doubt was received with great joy.

Very soon, after his return, I saved hard and left for the UK.

Only a few years later he died of a heart attack, I think.

For me, whose life had been disrupted at the age of 16 when he withdrew his pension and left for England and never having a real home after that, his death was a relief. I no longer had to hide my feelings or inability to explain who, where or what he was.

Now I can, at last, look on him as a self centred, driven, ultimately pathetic, sad, but charismatic man whose mission to save the world was not wanted by the world – and a restless, very ambitious man whose wife never gave up on him in spite of his love of other women and presumably affairs with some …